To the editor: Taking refuge at the spectacular collapsed caldera of volcanic Deception Island in Antarctica was one of the highlights of our trip to the southernmost continent. We were eight sailors, mostly from Maine, on a three-week voyage on Skip Novak’s 74-foot sailing vessel Pelagic Australis. The passage took us from Puerto Williams, Chile, to the Antarctic Peninsula and back in February of 2014.

Our passage south was an uneventful three days of mostly motor sailing that ended in heavy winds. Our course was well to the west of the rhumb line since, in general, passages between Cape Horn and the Antarctica Peninsula stay west due to the prevailing winds and the constantly east-flowing current. The current would carry us east and the winds preceding an incoming low would allow us to ease sheets and reach to our first Antarctic destination, Deception Island.

We made it into Deception Island ahead of an approaching low-pressure system and anchored in the sheltered Stancomb Cove the first night. We moved the next day and anchored off the beach in Whalers Bay, opposite the site of one of the largest early 20th-century whaling factory ship anchorages in Antarctica. As many as 10 factory ships might have been anchored where we were, processing whale blubber and bone, seals, guano and who knows what else as efficiently as possible.

|

|

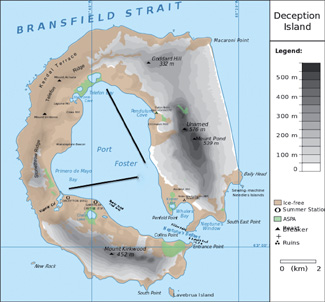

Deception Island, Pelagic Australis maintained track A during the storm and the Argentine naval vessel track B. |

What made Deception Island attractive then and now is that it was a huge volcano whose caldera collapsed. Entry into the caldera is via a narrow, perhaps 600-foot wide, passage. Inside is a large (about 5.6-by-3.7 mile), extremely sheltered harbor. The volcano is still active, having blown last in 1967 and 1969 wiping out a number of research stations.

As our British captain Magnus Day nosed Pelagic Australis close to the beach, a few of us glanced at each other wondering why he was getting less than three boat lengths from shore. In Maine we would never get this close because of the shifting tidal currents and the possibility of a change in wind direction overnight. One of us was bold enough to question his move and he explained to us Antarctica newbies that, one, the winds never change direction down there; two, there is no tidal current to worry about; and three, distances off are very hard to read in Antarctica. For that reason he frequently refers to the rangefinder slung around his neck when nearing land. We were safe.

But we weren’t safe. The low we beat to get into Deception Island slowed and brought us 45-knot winds which caused the anchor to drag. Hauling in the anchor in an attempt to reset it overheated the windlass so Magnus chose to power in position while it cooled. But the winds increased, so he then decided to reach under bare poles in the bay, powering up to come about before reaching back.

At first we had the entire bay to ourselves, but an Argentine naval vessel anchored off their research station in Primero de Mayo Bay and also dragged its anchor. Magnus and the Argentine captain agreed, via VHF, that Pelagic Australis would jog mostly north and south in the lee of the rim while the ship would jog mostly east and west, never crossing one another’s track.

During the night the winds peaked at 66 knots, near hurricane strength, but we were sheltered in the lee of the mountains to the northeast so had not much in the way of waves. Our motion was as comfortable as could be expected in 40- to 60-knot winds. I asked Magnus what he would do if the engine died. “Run it up on the beach, hopefully in Stancomb Cove.”

The next morning, 20 hours after dragging our anchor, the low moved on and winds calmed down to the point where we could depart the shelter of Deception Island to finally begin our two-week exploration of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Two nights before making our return to Chile from the Antarctic Peninsula, during dinner, we had westerly winds in the mid 20-knot range. The comments around the table, as we ate an incredible batch of Chilean ribs, ranged from “Glad we didn’t get any heavy weather,” to “Wish we had at least one dose of typical Southern Ocean, Cape Horn weather.”

|

|

Capt. Day at the helm. |

|

John Eide |

Before leaving the Ukrainian Vernadsky station in the Argentine Islands, 50 miles north of the Antarctic Circle, Magnus had been checking the GRIB files twice a day to plan the best course and, more important, the best timing to get us back to Chile with the least engagement with any heavy weather.

We got our heavy weather. Just before Joel and I came on watch at 2200, the previous watch took in the genny and set the Yankee and staysail. Just after we came on, we put a double reef in the main and rolled in the Yankee. An hour later, we put in a third reef and kept the staysail. The new weather system had arrived and brought with it a steady 35 knots or so with higher gusts. We were 10 hours south-southwest of and heading for Cape Horn.

A low was forming off the west coast of Chile and was expected to hit the Horn just about the time we arrived. Delaying our departure to pass behind the low would have meant a few day’s delay, missed plane connections and who knows what else. Leaving now meant an uneventful sail across the Drake Passage with the chance of meeting the leading edge of the low as we arrived at the Horn.

The Southern Ocean is notorious for the deep lows that ceaselessly circle the Antarctic continent that produce steep waves — especially in the Drake Passage where the waters shallow quickly — combined with the fairly strong easterly current that flows around Antarctica.

The course Magnus charted had us leaving the Argentine Islands and heading pretty much northwest, well west of the rhumb line. His goal was to gain as much westerly as possible early on so that when the low came, and with it the northwest winds, we could then bear off and reach our way to the shelter of the islands north of the Horn. Magnus wisely chose to leave promptly and take our chances on the other end.

We flew past the Horn in 45-knot winds with no chance of landing on the famed Cape Horn Island or gaining any shelter in nearby coves. Once within the shelter of the islands between the Horn and Puerto Williams, winds were fairly calm for what was an uneventful sail to home base. Looking astern, however, we saw the impressive cloud formations created by the 80-knot winds. Tose were a sign that we had missed the worst of the weather.

—John Eide sails his 1958 Concordia yawl Golondrina out of Portland, Maine.