On a displacement cruising boat, the quickest way to travel from point A to point B is still a straight line. Cruisers sometimes get caught up in sailing gybing angles, thinking the extra speed will make up for the extra distance sailed. It’s (usually) not the case.

Magnus Olsson, the legendary Volvo Ocean Race sailor, crewed aboard a Baltic 64 in last year’s ARC rally. I met him in Stockholm, Sweden, in August and he explained to me the vast difference between cruising and racing boats.

|

|

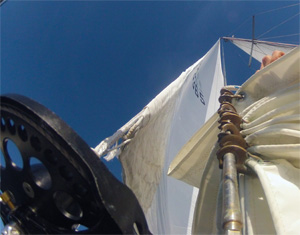

Mia Karlsson Twin headstay rig, showing Colligo furler and hank-on genoa. |

“A boat like Triumph, that is so heavy, it doesn’t pay to come up 20 or 30 degrees from dead downwind,” Magnus Olsson explained. A difference of 30 degrees true wind on a Volvo 70 is incredible in a breeze. “It’s eight knots!” Olsson exclaimed. The Volvo 70s will sail 20 knots at 150 true, and drop to 12 knots dead downwind. “By heading up 30 degrees, you get so much more speed! Which doesn’t ever happen on cruising boats.”

“It does not pay because you don’t get faster,” he continued. “So a typical cruising boat in 20 knots of wind, you always sail, if you want to go fast, VMG downwind. You go very close to dead downwind.”

White sails to leeward

The most unique twin-headsail approach I’ve seen for downwind sailing was on Canadian sailor Yves Gélinas’ Alberg 30 Jean-du-Sud. Gélinas is the inventor of the Cape Horn Windvane — he tested his prototype gear during his attempt at sailing nonstop round the world via the five great capes, and had Jean-du-Sud set up for ease of handling.

Jean-du-Sud has twin headstays, rigged athwartships of each other. One is a plain wire stay and accepts hank-on sails, while the other is a traditional roller-furler. Gélinas primarily uses the furler, but in heavy weather or when running with twin jibs, he can hank-on an equal sized genoa on the bare stay and have loads of flexibility on the foredeck.

On our 1966 Allied Seabreeze Arcturus, we use a similar but slightly more modern approach. I also have hank-on headsails, but we carry a cruising Code 0 that flies on a Dynex Dux luff and rolls around a Colligo continuous-line furler that tacks to the reinforced anchor roller (or could be tacked to a bowsprit). Under normal sailing conditions, the sail can remain hoisted and rolled, while we use the jib on the headstay. In light weather we can run with twin genoas, one on the stay in combination with the Code 0. And when the wind gets up, the furled sail can be lowered and stowed belowdecks where it really belongs.

Perhaps my favorite white sail combination came on my last Atlantic crossing on the Saga 43 Kinship. The boat was solent-rigged, and with the wind on the quarter in light air, we were able to fly the genoa and mainsail to leeward, and pole out the solent jib to windward, making seven knots boat speed in seven knots true windspeed. It only worked on a very narrow wind angle, but it worked nonetheless. The lesson in that is simply to experiment.

|

|

Mia Karlsson Sheeting jib to mainsail boom. Note mainsheet, preventer and topping lift stabilizing boom. |

The mainsail boom

To me, the ocean cruising yacht ought to carry a spinnaker pole. But if they don’t, there is an alternative. Lin and Larry Pardey, Hal Roth and Don Street have long spoken of using the mainsail boom as a pole. But a lot of modern yachts I’ve found don’t provide any means of running sheets and preventers at the end of the boom.

During our ARC Europe Atlantic crossing on Kinship, we lashed strops to the end of the boom for attaching the preventer and a block for the jib sheet. The boom is great as a pole because it’s already rigged — simply hook a preventer to the boom end and take up slack as you ease the sheet out. Adjust the topping lift and vang to get the correct height for a clean sheet lead. Run the jib or genoa sheet through that block and to another block on the toerail before bringing it back to a winch.

The owner of Kinship actually came up with a clever and elegant solution to replace the temporary strops. In Lagos, Portugal, he had a local machine shop make a stainless plate that he bolted to the end of the boom. The plate had several attachment points — one on either side for preventers, one for the topping lift and a fourth for attaching the sheet block when using the boom as a pole. It cost him $70 installed.

We used this setup extensively in the far north Atlantic on Arcturus when we had too much wind aft to use the mainsail. And on our second crossing on Kinship, the owner was so pleased with the setup that he felt the boat would be stable enough under that rig – with the solent jib sheeted to the mainsail boom, sailing dead downwind — to keep moving in 40 knots of true wind. We touched 13 knots on several surfing runs one night and never felt the slightest bit out of control — the autopilot steered throughout.

Boom preventers

Boom brakes are not boom preventers. Yes, they’ll slow the boom down as it gybes, but it will still gybe. I feel that preventers are still imperative safety-wise, can be used in conjunction with a boom brake, and most importantly, stabilize the boat downwind.

A proper preventer serves three purposes — it stops the boom from accidentally gybing, it stabilizes the mainsail off the wind, and properly rigged, it lowers the risk of breaking the boom if you dip it in the water.

|

|

Mia Karlsson |

|

All white sails flying on Kinship, a Saga 43, in mid-Atlantic. Solent jib is sheeted to windward. |

Kinship had a good system — the spinnaker foreguys were permanently led on both sides of the deck. They clipped to eyes on the bow pulpit when not in use, led around blocks right at the bow, and could be easily led aft and to the boom end when used as a preventer. The key is to lead the preventer all the way to the bow and all the way to the boom end. If the boom end dips during a roll, the force will be on the preventer line, and the longer that line, the more give and the greater the angle.

The best preventer system I’ve seen was taught to me by my former boss, Mike Meer of Southbound Cruising Services in Annapolis. Meer rigs permanent foreguys as on Kinship, then leads a length of Dyneema down each side of the boom, affixing them on padeyes aft. The Dyneema is lead forward and clipped to the boom just before the gooseneck. The foreguy is then lead to the goose-neck end of the Dyneema, and the lines are clipped together — the advantage is that prior to a gybe, the opposite preventer can be rigged from the gooseneck rather than leaning out over the water and trying to reach the boom end. The Dyneema acts as a permanent messenger line.

Wing-on-wing

By far our favorite downwind sail combination on Arcturus’ Atlantic crossing was the small jib set on the spinnaker pole with a double-reefed mainsail. Like the owner discovered on Kinship, sheeting a headsail to a solid spar drastically stabilizes both the sail and the boat. You get none of the flapping and chafing of trying to sail downwind with a loose genoa, and none of the frustration of trying to steer on that ‘edge’ when broad-reaching.

If you’re not adhering to any racing rule, get the longest pole you can fit on the boat. Carry two different sizes if possible, and stick to heavier spinnaker poles rather than the lighter whisker poles. Nothing too strong ever broke.

A longer pole allows you to set a bigger sail from it. To expose the maximum sail area to the wind, headsails should be flat — the most extreme example is the old square riggers — and to get the foot of a big genoa flat, you need a long pole. As with spinnakers, the pole ought to be guyed so that it’s stable without the pull of the sheet.

|

|

Mia Karlsson |

|

Rigging Kinship’s new symmetrical chute en route to Las Palmas during an Atlantic crossing. |

In heavier weather, our spinnaker pole was long enough to sheet our 100 percent jib on Arcturus perfectly flat to windward. By moving the end of the pole forward, we could actually project the sail forward of the boat, and keep sailing wing-on-wing up to about 100 degrees apparent. It was versatile and stable, and saw us more than halfway across the Atlantic.

Spinnaker sailing

Too often I read about foregoing spinnakers offshore. I understand that it’s a conservative attitude, but I believe it’s wrong. The late, legendary Hal Roth would have agreed with me:

“The ideal sailing vessel needs clouds of sails in light airs,” he wrote. Roth and his wife Margaret sailed hundreds of thousands of miles in various yachts called Whisper, from Cape Horn to Alaska, Japan and into the Mediterranean.

“If you don’t put up lots of sails, you’ll never get anywhere.”

About 10 days into our passage from Bermuda to Horta on Kinship, I’d finally convinced Tim that he needed a light-air, downwind solution. The west-east passage gave us a little bit of everything — heavy and light weather, reaching and a bit of upwind sailing — but Tim’s return trip with the ARC would be a classic tradewind passage — with luck, a dead run 2,800 miles from Las Palmas to St. Lucia. I ordered him a symmetrical chute from Chesapeake Sailmakers in Annapolis, and they custom cut it slightly smaller than a racing chute and sewed it from heavier cloth. On a passage from Portugal to Las Palmas in September, we flew it in light weather and Kinship came alive. Previously on such occasions, Tim would have motored. He doesn’t do that anymore; he sails.

Arcturus is only 24 feet on the waterline — and lacking in storage — yet we carry five headsails. And we use them all. My favorite is the 1960s vintage blue-and-white racing chute that we used for several days north of 50° in the North Atlantic. The wind was light, the weather settled and the sail propelled us along on a flat sea far faster than any white sails would have.

As Olsson stressed to me in Stockholm, displacement cruising boats simply cannot sail fast enough to make up the added distance that gybing angles create. For most boats, the fastest way downwind between two points is a simple straight line. And for that, you need real spinnakers.

|

|

Mia Karlsson |

|

Running before the wind sailing wing-on-wing while approaching Ireland aboard Arcturus. |

I’ve learned that safe and efficient spinnaker sailing requires a solid spinnaker pole setup — rigged to the mast, where one end is always attached — and a sock or a spinnaker furling system like Profurl’s new Spinex setup for stress-free setting and dousing the sail. And lots of practice. Having the foreguys permanently rigged as on Kinship is an added bonus, and makes it possible for one person to set and douse the pole on the foredeck.

It’s all about patience and process. Go over each step of setting the pole and rigging, hoisting and setting the sail. Talk it through before you do it, and practice it on calm, light air days. Rig the pole with fore and aft guys, a topping lift and if needed a downhaul so that it stays put even without the spinnaker sheet. You should be able to set and douse the chute while the pole stays stable.

Parasailors are becoming increasingly popular on cruising boats as well. I’ve seen them on everything from Swans and Oysters in the ARC, to a Westsail 32 on the Chesapeake. Marc Elbet, a French sailor we met on the ARC last year, finally caved and is planning on buying one for his third Atlantic crossing in two years. Elbet sails a solent rigged OVNI 471, and has previously sailed downwind wing-on-wing. But he hates spinnaker poles, and is intrigued by the Parasailor’s ability to sail downwind without one.

Olsson summed up the downwind game rather bluntly during our chat in Stockholm. “If you sail a Volvo 70 the ‘right’ way around the world, based on the VPPs, you go so fast, your apparent wind angle will always be 90. That’s so different to cruising,” Olsson said.