|

One of the oldest debates in the sailing community surrounds the essential features of a bluewater boat. We found ourselves in the midst of this distracting deliberation when we set ourselves the goal of sailing from Vancouver to Australia. Knowing very little about what we were embarking on, we joined the Bluewater Cruising Association and asked as many people as we could about what we should be looking for in an offshore yacht. In the Pacific Northwest, the consensus seemed to be that the “bluewaterness” of an offshore yacht boiled down to six main elements: a long keel, a skeg-hung rudder, heavy displacement, reputable offshore builder, large water and diesel tanks, and a cutter rig or ketch design.

This legitimacy of this list was bolstered by John Neal’s tips on what to look for in an offshore cruising boat (www.mahina.com/cruise.html) and especially his list “Boats to Consider for Offshore Cruising.” We paid attention because John Neal has sailed more than 350,000 miles — including six Cape Horn roundings — and is considered a leading expert in offshore sailboat preparation.

As we looked around for a suitable sailboat, we were dismayed to find that very few had all the characteristics that were recommended and almost none in our price range. The ones that did felt so old and clunky that we couldn’t imagine enjoying sailing them. As one enthusiastic seller said to us, “Takes her 20 knots of wind to start moving, but when she does, she’s a freight train.”

What’s out there?

We began to ask questions. “Do we really need a full keel?” “Can we get by with a spade rudder?” In the end, we went with a boat that met some of the requirements but not all. We settled on a Dufour 35, built in 1979. It had a solid fiberglass hull and a rudder protected but not hung by a skeg. The boat was billed as a racer-cruiser when it came off the assembly line; as such, the tankage was minimal, she doesn’t have a full keel and isn’t a cutter. She also has a balsa-core deck to save on weight, something John Neal says to be careful of. We were emboldened by the report that many others had sailed around the world in this model of boat and she did appear in John Neal’s list of acceptable offshore boats, although without glowing remarks.

We were never fully confident in our little Dufour as an offshore vessel until we got to the Marquesas. It wasn’t only that she got us there in one piece, but more that upon arriving we saw boats of all ranges and shapes. We saw new Beneteaus and Jeanneaus and even Hunters and Lagoons — all light displacement, fin keel, spade rudder, no bilge, fractional-rigged sloops. “What’s going on?” I asked myself. “How did all these non-offshore boats get here?”

Intrigued by this surprising revelation, I endeavored to learn more about what kind of boats cross the ocean. I gathered data from 56 boats that crossed the Pacific between 2016 and 2017, and researched their features to see how many checked the boxes on the bluewater list. The results called into question the traditional perspective and reflect the new era of weather forecasting and navigation.

By the numbers

Of the 56 boats examined in this study, nine (16 percent) met all the aforementioned criteria for a bluewater boat. On average, the boats met 41 percent of the criteria. One boat met none of the criteria, and 15 boats (26 percent) only met one criterion. Eighteen boats that crossed — just under a third of those surveyed — are on John Neal’s list of preferred boats for offshore cruising.

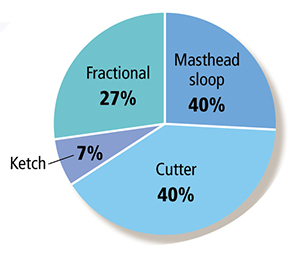

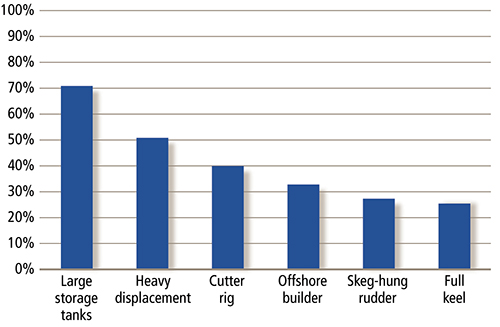

The chart at the bottom of the page gives the relative breakdown of boats by criterion. The two most often met criteria were large storage capacity and heavy displacement, which are usually linked. Cutter rigs were popular designs, while ketches were few and far between. A full discussion of each feature is included below.

|

Rig types

The most common rig type turned out to be a cutter rig (40 percent), followed by fractional rigs (27 percent) and closely thereafter by masthead sloops (26 percent). The more modern light-displacement boats usually feature fractional rigs. Ketches (7 percent) filled out the rest of the fleet.

The main advantage of a cutter rig is the ability to fly a staysail or storm jib from the inner forestay, which provides more options for both light wind and heavy weather. Keeping the center of effort close to the center of the boat is more efficient and more comfortable in heavy weather. The secondary advantage of a cutter is having a backup forestay already installed should the main forestay fail. Owners of masthead sloops often install Solent stays to provide some of the same benefits of a cutter. We did this, but in the end it only gets in the way and we never use it.

The main advantage of a fractional sloop is easier sailing and handling. The jib is smaller on a fractional rig than a masthead rig and makes gybing and tacking easier. Also, the spinnakers tend to be smaller on fractional rigs and easier to fly for most cruising couples or shorthanded crews. As wind speeds pick up, the main is reefed while the jib can remain full up to certain wind speeds. This makes reefing easier and improves efficiency as reefed headsails have notoriously poor shape and move away from the center of effort as they are reefed.

|

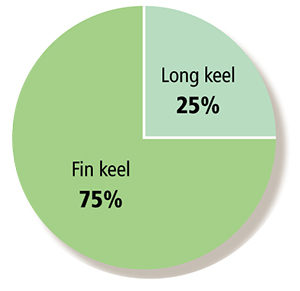

Keel types

For the purposes of this study, keel shapes weren’t defined beyond long keel or fin keel. Cutaway forefoot and full keels were grouped under long keels, and winged keels or bulbed keels were grouped under fin keels. Only a quarter of the boats had long keels. As seen with the fractional rigs, modern designs overwhelmingly use a fin keel to provide lateral resistance. More than 13 percent of the boats were catamarans and don’t really fit into either category.

A long keel has many advantages and many detractors. A full keel is usually encapsulated in the hull, making the connection much stronger than a bolted-on fin keel. A long-keel boat is easier to make heave-to, as it doesn’t pivot on the keel the way a fin keel does. Also, a full-keeled boat tracks better, especially going downwind in large seas, preventing the roundups on waves that are associated with many fin keel designs — ours included. The main detractor of a long keel is that it is much less efficient than a fin keel, which means significantly reduced boat speed. It also makes tacking or gybing more difficult and sometimes impossible in light air with a full keel. The same problem extends to motoring around the marina or anchorage, where the long keel makes quick and tight turns difficult.

|

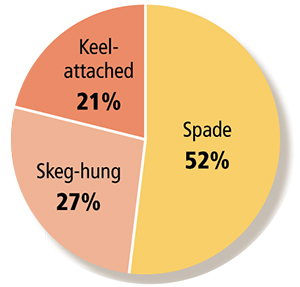

Rudder

A slight majority of the boats had spade rudders (52 percent). The rest had skeg-hung (27 percent) or attached (21 percent) rudders. In 2017, five of the boats in this study developed rudder issues during the crossing. Two spade rudders delaminated and one seized, while the two skeg-hung rudders developed leaks around the rudderposts. Most of the boats with spade rudders I surveyed did not strengthen their rudderposts but left the factory post in place.

Skeg-hung and attached rudders have an obvious advantage in that they are protected from direct impact. The pressure on the leading edge of the rudder is also greatly reduced, putting less strain on the rudderpost. An added advantage is that fishing lines and other marine debris can’t get caught in between the rudder and the hull. As with a full keel, the main detractor is diminished sailing performance. A spade rudder acts like a wing under water. It’s ability to cant with the turn and its fine leading edge make it much more efficient than a skeg-hung rudder. The rudder design makes the boat more responsive to changes in course as well as enhancing overall speed.

|

|

|

Urquhart looked at a number of design issues, such as whether a boat had a fin keel or a long keel and was equipped with a spade, skeg-protected or keel-hung rudder. While spade rudders are the most vulnerable to impacts with debris, most of the boats in the survey were equipped with them. |

|

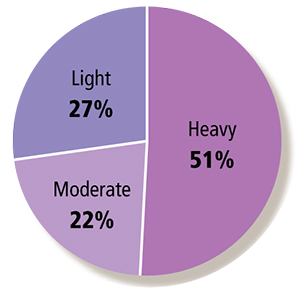

Displacement

The definition of heavy displacement is anything with a displacement/length ratio (DLR) of 270 to 360. Moderate displacement is anything between 180 to 270, and light displacement is any DLR less than 180. Roughly 51 percent of the boats that crossed could be considered heavy displacement. The rest mirror the rig types, with 27 percent falling into the light displacement category and 22 percent under the moderate displacement label.

|

A heavier boat will be more comfortable in heavy weather and is usually more robust all around. One of the Dufour 35s (moderate to heavy displacement) that crossed in 2017 had just completed the Northwest Passage where it collided with an iceberg at 7 knots and suffered absolutely no damage. Similarly, a CT 41 (heavy displacement) this year hit a coral head at 6 knots and received minimal fiberglass damage at the front of the keel.

But heavy also means slow, especially in light air. A fast boat can sail through conditions in which a heavier design would languish or be forced to motor. It can also move more quickly and often avoid weather systems. While you might not want to get caught in a storm in a light displacement boat, the view is you might not have to.

Reputable offshore boatyard

Defining a boatyard as a “reputable offshore boatyard” is a dangerous and ultimately futile exercise. Beneteaus, Jeanneaus and Lagoons made up 20 percent of the boats in the survey group. They are reputable boatyards but are not known for making offshore boats. The rest make up the gamut of other builders, including Deerfoot, Dufour, Fountaine Pajot, Hans Christian, Hunter, Island Packet, Lapworth, Morgan, Ovni, Pacific Seacraft, Tartan, Valiant, etc. Some are known as offshore builders, while others are not. As was noted previously, only 33 percent were on John Neal’s list of recommended offshore boats.

Large storage capacity

This is one criterion that seemed to be consistent across the board. Seventy-one percent of the boats were listed as having relatively large factory-built water and fuel storage capacity. Boats that don’t have large factory-built tankage are often augmented for long-distance cruising. Our own Dufour has had a diesel tank added and two water tanks to make it more comfortable on long passages, as well as having extra cabinetry installed. Friends of ours on a newer Dufour make up the difference with umpteen jerry jugs to hold diesel and water.

|

|

A chart from Urquhart’s cruising survey showing a breakdown of boats by criteria. Understandably, large storage capacity was the criterion most frequently met. |

Why the discrepancy?

The list of boats that successfully made it across the Pacific in the last couple of years does challenge the traditionalist perspective about essential offshore elements. What explains the discrepancy between what we think should be crossing an ocean and what is actually crossing? The most likely explanations are: weather forecasting and preventative maintenance.

Weather forecasting and GPS

The difference between the traditionalist perspective and what we are seeing offshore nowadays might be explained by technological advances — specifically, access to better weather forecasting and the advent of GPS. These combined mean that, for the most part, heavy weather can be avoided, especially the big lower pressure systems. It is rare in the current era for a boat that has access to daily weather forecasts to get caught by a large storm. For heavy weather avoidance, the big slow boats are at a disadvantage because they can’t use light winds to sail through large areas and might not be able to move fast enough to avoid an approaching system. The longer a passage takes, the more exposed the boat and crew are to inclement weather.

Based on data gathered from more than 150 boats that crossed the Pacific in the last six years (2012 to 2017), the average maximum reported windspeed was 32 knots, with 82 percent of boats reporting maximum windspeeds of less than 40 knots. The high windspeeds were almost always due to squalls around the equator and lasted less than 40 minutes. Almost any boat can handle this windspeed and the accompanying sea state.

Preventative maintenance and spares

So many of the problems associated with any boat can be avoided through regular maintenance and checkups. Small issues can often be easily managed with the right spares and tools before they become larger catastrophic problems. This rule applies to all boats, whether they are going offshore or not.

Of the 150-plus boats that crossed in the last six years, only 16 reported no significant breakages during the crossing and the overwhelming reason touted by these sailors was preventative maintenance. The rest who had significant gear failures were usually able to manage a repair at sea. Only a few were towed into port and none were abandoned.

So what actually makes a bluewater boat? You do. It is neither my intention to end the bluewater boat debate, nor to recommend one style over another. Windspeed and sea state are not the only factors to consider when offshore cruising. There are also fishing lines and nets, coral heads and other obstructions, constant wear and tear on gear, comfort below decks, galley design, sea berths and many other factors. Picking the right boat for offshore cruising is a personal choice. Most important is that you know the boat and feel comfortable sailing her in a variety of conditions.

Robin Urquhart is a live-aboard voyager who cruises with his partner, Fiona McGlynn, aboard their Dufour 35 Monark. For more, see www.happymonark.com.