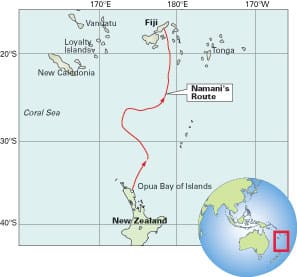

There’s the rhumb line, the great circle route, and there’s the long way around. The latter wasn’t exactly our intention when departing New Zealand for Fiji one late May day, but that’s what sailing is about: life at the mercy of the elements, sometimes for better, sometimes for worse.

It had been a wonderfully unambitious season in the land of the kiwi for me, my husband Markus, and 9-year-old son, Nicky. Once that cyclone season passed and winter was coming on, however, we were eager to explore “the Islands,” as Tonga, Fiji, Vanuatu and New Caledonia are fondly referred to. Apart from shaky sea legs, we wondered, how complicated could this be? The passage is simply the Southern Hemisphere version of the U.S. East Coast to Caribbean run, without the complication of the Gulf Stream. No problem for Namani, our 1981 Dufour 35.

Our suspicions, however, were aroused by a contradiction: while respected sources such as Jimmy Cornell and the Island Cruising Association Rally give late April/early May as a good departure time, most veterans wait for more stable weather patterns in June — that’s winter, meaning an increased frequency of Tasman Sea lows. So which would it be: an early start, toeing the line with the end of the cyclone season, or a later passage, with a trade-off between more reliable weather and colder temperatures?

|

|

Markus does a pre-departure check of the rig in Opua, New Zealand. |

Searching for an opening

We spent nearly all of May in the Bay of Islands, finding no sign of what we would call a weather window. Boats that did depart early ran very narrow gauntlets between high latitude storms and tropical depressions that seemed determined to keep all intruders out of their territory above 25° south. Some crews got lucky in their gamble; others, not so lucky. We listened in to the radio nets and felt justified for hanging back while others reported 30-, 40-, even 50-knot sustained winds with seas to match. One friend reported: “Arrived in Fiji a little blown away, but all in one piece.” The boat, however, was “in a few more pieces,” including a broken pushpit, a parted genoa sheet, and torn lazy bag. Meanwhile, we were happy and well occupied in New Zealand’s beautiful Bay of Islands. Why rush off?

For a good passage north, we wanted the back side of a low-pressure system moving east across the Tasman Sea; the leading edge of the following high would provide favorable winds up to the trade winds. In the long-term forecasts, the systems all looked promising while they built over Australia. But as time passed and the systems inched closer, they either morphed just enough to postpone our departure, or the South Pacific Convergence Zone would spawn another late season tropical depression. Time and time again, we thought we had our window and prepared for departure. The boat was ready, the crew was ready, even the vegetables were ready. But what were optimistic weather windows to begin with inevitably took a turn for the worse: the high a little too weak, a little too short; or an unstable tropical depression would pop into the scene like a loose cannon. All in all, the science of forecasting seemed more like a dark art of consulting oracles and reading entrails.

|

|

Namani departs the Bay of Islands in ideal conditions. |

And so we waited, and waited, and waited. Lovely as New Zealand is, the island nation was taking on a Hotel California feel: you can check out any time you want, but you can never leave. Thirty-five-plus knots on the beam with 20-foot seas, anyone? What about four days of strong northerlies, followed by a week of motoring? There were, in fact, a few takers for each of these “windows,” many of them crews with looming visa expiration dates. We bit the bullet and applied for a visa extension instead. What’s NZ $165 versus an unnecessary thrashing (and possible gear damage) at sea? As a consolation, all those perfect New Zealand anchorages were now empty of other cruisers, so we were content to wait on.

It was late May and a full month after our intended departure time before the weather systems stabilized enough to put any faith in the forecasts. Finally, we had it: a low followed by a nice, strong high that would bring us into the trade winds with reliable southeasterlies. Yes, there was one tropical depression out there, but every available forecast model consistently had it tracking well ahead and out of our path before it caused any trouble. A period of northerly winds carried in by a cold front could be dealt with by stopping over at Minerva Reef. It all looked very manageable.

In good company

During our weeks of waiting, we had the feeling that we were stragglers, the softies left behind while all the other kids had gone out to play. But it turned out we were in good company, as evidenced by the sight of 30 crews queued up outside the Opua customs office on the morning of Wednesday, May 29. The atmosphere was one of an excited high school graduation: all hugs, sentimental retrospection, and eager looks forward into a warm, tropical future. Soon, the Bay of Islands was sprouting with more sails than we had seen in a month, an entire armada heading for various points north.

|

|

Namani flying only its “baby” staysail in rough conditions. |

It all looked so good on that gloriously sunny afternoon. Initially, everything unfolded as expected, with a nice southwesterly breeze to carry us away from land. As night fell, so did the wind, just as forecast. We piled on layers of warm clothing and cranked up the motor. Never had leaving land for the open ocean seem so easy!

Until it got complicated, that is. That lurking tropical depression surprised everyone by taking its own good time to materialize. Instead of being swept away in front of an east-bound high, the cheeky thing slipped in behind the high and suddenly stood directly over our route. While some crews plowed straight on (eventually reporting sustained 50-knot winds and heavy seas), most detoured west to skirt the edge of this low. A stopover in Minerva Reef was no longer an option, so we steered Namani on a new heading of 330° to avoid the worst. Even with a detour that took us as far west as 173° 02’ E, we hit 40-knot winds and rough seas. Happily, both came from behind and the boat rode it out well, even if our stomachs didn’t. For 48 hours, we subsisted entirely on pretzels and granola bars and simply hung on. Namani made a solid five and six knots, even when we struck the main and genoa to sail under our “baby” staysail — a pitifully small scrap of canvas we were sure we would never, ever have to use. We were repeatedly soaked by slapping waves, and many crews bailed swamped cockpits after being pooped by following seas.

All the while, sea birds soared overhead, then swooped through deep troughs of short-period waves, just a walk in the park as far as they were concerned. For us, it was an unpleasant two days that ultimately gave us more confidence in our vessel and ourselves, if not in interpreting apparently “stable” weather systems — especially those fickle tropical depressions! As the wind gradually abated, we headed back to the east. Nature gave us a day off, with wind dropping to below five knots and seas rapidly easing.

|

|

Markus takes a peek over the dodger as Namani romps along under a triple-reefed mainsail. |

The Tsar’s thumb

Our 300-mile detour reminded us of the fanciful story of the Tsar’s thumb: once upon a time, Russian Tsar Nicholas I ordered his engineers to build a railroad from St. Petersburg to Moscow. He took a ruler and drew a straight line connecting the two points on a map — straight except for where his thumb jutted over the ruler, creating a slight bump. Not willing to question the Tsar, the engineers designed exactly the railroad he drew, including a mindless detour to nowhere. (The story is not true, it was reportedly concocted by the 19th century Russian writer Nikolai Grech, but it does illustrate the tendency of people to blindly obey authority.) Namani had traced her very own version of the Tsar’s thumb, but at least it allowed us to avoid the worst conditions!

We used the 24-hour calm after the storm to dry out, rest up, and chow down before the next challenge arrived. That was an approaching cold front that would sweep in a period of 20-knot northerlies expected to gust 35 to 40 knots — an “XL” version of the contrary winds we had originally hoped to sit out at Minerva Reef. The good news was, it was an opportunity to make back our easting by taking the wind on the beam, this time under triple reefed main and the baby staysail. The cold front hit in one nasty squall line. One casualty of the fray included the winch handle we keep at the mast, flipped overboard by a flapping sheet. Call it a token sacrifice to Poseidon! Another boat reported a shredded genoa and torn mainsail; they eventually limped in to port a day behind most others.

So what does a 9-year-old do while all this is going on? Nicky was largely unperturbed, putting supreme confidence in his parents and the boat. (Yikes!) He nonchalantly continued to read or ponder the computer programs of his dreams in his snug den of a quarterberth, making only brief appearances in the soggy cockpit. He did, however, confess to feeling a little bored. The highlight, as far as Nicky was concerned, was our high speed, topping out at nine-plus knots “downhill.”

|

|

Markus and Nicky prepare Namani’s inflatable dinghy after arriving in Savusavu, Fiji. |

Our second bout with the elements lasted 24 hours before the wind dropped and backed from north to northwest, west, and eventually, the southwest. Dawn brought the happy prospect not only of abating winds and seas, but sunshine, too. Given warmer temperatures and calmer seas, we finally had the pleasure of sailing with the companionway open. As the wind went to WSW and fizzled to 10 knots a few hours later, we pulled out yet another sail from our arsenal of six: the Parasailor, an excellent light wind sail that significantly reduces the boat’s rolling motion — a major plus in the confused slop left in the wake of the preceding systems. The galley filled with the aroma of fresh bread and muffins, and the general scent aboard was further improved after salt water baths for each of us in our inflatable kiddie pool, followed by a fresh water rinse. Markus used a stranded flying fish as fresh bait and promptly snagged a big mahi mahi, giving us a real dinner treat. Yes, passagemaking certainly has its pluses and minuses!

Just a day later, Namani reached the trade winds for good: reliable 15-knot winds from the southeast. The radio net sang with a chorus of relieved voices from crews finally making good progress in the right direction. We benefited greatly from two friends outside our little flotilla: one was a ham radio enthusiast and sailor in New Zealand who used his home Internet connection to fill us in on satellite images of the various weather systems. Another was a sailor already at our destination (Savusavu in Fiji), who added each of us to the waiting list for moorings in tightly packed, deep water Nakama Creek. Thanks to him, all the boats in our little pack of six could be accommodated upon arrival. Fifteen months earlier, we had started our Pacific crossing feeling very much alone; now, we were part of a tight network of sailors who truly looked out for one another.

As it turned out, none of us were in a particular rush to arrive, since Fiji customs officers charge high rates for weekend overtime. Several early arrivals hove-to for 48 hours rather than paying the additional fee. Namani was well on track for a Monday morning arrival, so we could fully enjoy the last section of what would be a 12-day passage. With no excuses left, home schooling was back on the agenda, along with reading and guitar playing. The moon had gradually faded from its third quarter to a thin crescent during our trip, leaving a sky full of brilliant stars. Prominent among them was Scorpio, clawing its way up into the night sky, and later nose diving into the western horizon.

A straightforward approach

The main challenge left was navigation as we approached the islands of southern Fiji. Sunday was a day of ticking off progress past large islands as we made our way north. In this area, the islands are widely spaced and mercifully free of isolated dangers, making the approach to Savusavu straightforward. It was only with a few miles to go that we put on our polarized sunglasses to run the reef-lined entrance into Savusavu Bay. No sooner had we made the turn into Nakama Creek than a launch from Waitui Marina came out to guide us to our mooring with a friendly hello — in Fiji, that’s a hearty “Bula!”

|

|

Fiji officials join Markus in the cockpit to review Namani’s clearing-in papers. |

The longest passage of our second Pacific cruising season was now behind us; we were back in the tropics at last, and could look forward to shorter hops all the way to Australia.

Including our detour around the Tsar’s thumb, Namani sailed 1,485 miles instead of a straight-line 1,140 miles. We spotted everything from small petrels to broad-winged albatross on the way from 35° S to 17° S, and flew four different sails over the course of this varied passage, from our biggest sail (the Parasailor) to the smallest (the baby staysail). We were especially glad that we had taken the time to do a test hoist of this sail back in New Zealand and that we’d stowed it within easy reach.

Having waited a long time for a good weather window, we admit to feeling a bit chagrined to find that our chosen slot was not significantly better than many earlier departure times we had rejected. In fact, we broke our own rule: never to assume anything about a developing tropical depression is predictable. On the other hand, we console ourselves with the fact that we had been tracking the two weather systems that disturbed our passage all along; when their paths did deviate from the forecast, we could quickly go to Plan B. Of course, we could have waited another few weeks in New Zealand, but sooner or later, every cruiser has to hit the road. And ultimately, that is what separates the boats at the dock from the ones sending tropical greetings home.

—————

Nadine Slavinski is the author of Lesson Plans Ahoy: Hands-On Learning for Sailing Children and Home Schooling Sailors (see www.nslavinski.com). Together with her husband and young son, she lives aboard her 1981 Dufour 35, Namani.