Our boat Astarte is a Moody 422 built in 1987, and it still has its original engine — a Perkins 4-108. We purchased the boat as the third owners in 2004. The boat did not have an engine hour meter, so we installed one immediately and have put almost 3,000 hours on the motor. The bottom line, though, is that we really have no idea how many hours are on this engine.

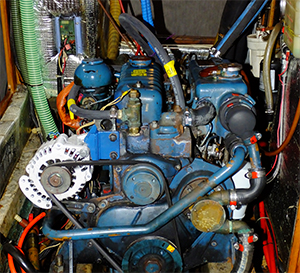

The engine gets lots of care and regular maintenance. Oil and all filters get changed every 100 hours, though some tell us that is more often than needed. Transmission fluid gets changed every 500 hours. Antifreeze is replaced periodically, and we keep a close eye on belts, hoses and any major oil leaks (it is a Perkins after all). The front and rear crankshaft seals were replaced in 2013, along with engine mounts. Raw-water pump bearings, seals and impellers have also been replaced when needed.

We have been fulltime cruisers aboard since 2009 and have covered a lot of territory since we left Florida. We did some time in the Caribbean and went through the Panama Canal in late 2011. Then we made the Pacific Passage from Panama to the Galapagos and on to French Polynesia, Niue, Tonga and New Zealand in 2012, followed by a passage to Fiji, Tuvalu, Kiribati and the Marshall Islands. The next season we did the Marshall Islands to Vanuatu and New Caledonia, then back to New Zealand. After this, we then did a repeat of Vanuatu and New Caledonia from New Zealand and returned to the land of kiwis and rugby.

Over the last few years, we have been having a few more issues with the engine and had started to lose confidence. In Bora Bora in 2012, we had a “runaway” caused by diesel fuel filling the crankcase. We thought we solved that issue by replacing the fuel pump, disconnecting the fuel line to the pre-heater and finally rebuilding the injector pump. But over this past season, we thought there might again be diesel sneaking into the oil. We also had an overheating issue that took a long time to track. We had pulled the heat exchanger the previous year and had it serviced but thought it was leaking. The problem, however, was a hose from the water heater to the engine, which ran under the floorboards (where we couldn’t see it) and had turned to “mush.” There was a diesel leak as well that was sorted by tightening some banjo fittings on the recently rebuilt injector fuel pump.

The last two problems happened simultaneously when we were in a very remote island in the Vanuatu chain. It made us begin to question whether we needed to continue to repair this old engine at about $1,000 each time, rebuild the Perkins or sell it and buy a new engine. Our confidence was rocked, and if we wanted to venture to more remote places in Indonesia, we wanted an engine we could count on.

|

|

The boat’s Perkins diesel. |

|

Michael Hawkins |

The process

We decided to be methodical in our approach to the decision to repair, rebuild or repower. We made a list of the costs and benefits of each option (see “Repair, rebuild or repower,” March/April 2016). The first step would be to really take a hard look at our existing engine and make sure we were not simply overreacting to two simultaneous problems. We hired a diesel mechanic in Whangarei, New Zealand.

Hiring a mechanic is a tricky proposition, especially away from your home port. When we were shoreside in St. Petersburg, Fla., we had “our guy,” Dusty Rhodes (really, that is his name). He was someone we knew and trusted. He worked on our previous boat with a Westerbeke 4-107 and helped us in replacing that engine with a new Yanmar 3JH. So, we did get some experience with replacing a main motor. The bad news was that we didn’t get the benefit of this engine as we sold that boat after a year of cruising on it, after deciding it wasn’t the right vessel for us.

We’ve had mostly good experiences with hiring mechanics … but also a few not-so-good ones. Sorting out a person’s skill and expertise can be difficult when you need the help. This can be especially difficult if there is also a language barrier involved; it might be worth an interpreter if the project is a big one.

We’ve found that the best way to score a good mechanic is by getting recommendations. Find out whom other boaters have recently used — especially local boaters. Boaters love to talk and they all have opinions, so getting names and their thoughts on the mechanics shouldn’t be an issue. Get several recommendations from people who have used various local diesel pros and find out in detail what was done. Talk to the potential choices yourself and see if they think the same way you do. For example, are you both looking for less expensive ways to solve a problem? Make sure they know your engine, though a good diesel guy should be able to fix any of them. You do have to be careful with hiring other boaters or even letting them work on your engine “gratis.” We met a boater in the San Blas Islands who told us he was a waiter in his land life; a few years later in Pacific, this same person was touting himself as a boatwright and mechanic. Most good diesel mechanics who are out cruising rarely mention that they have that skill — they are out cruising after all, and taking care of their own boat is plenty to keep them busy!

We also wanted a mechanic who would let Michael look over his shoulder and allow us to do some of the work. We can save money by doing a lot of the disassembly, shopping and simple assembly with good instruction. We can take parts to specialty shops to be checked out or rebuilt, like injectors or heat exchangers for example.

|

|

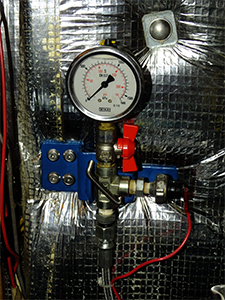

The mechanical oil pressure gauge installed by the mechanic in New Zealand so he could monitor the engine’s oil pressure. |

|

Michael Hawkins |

We found Tim Brown, a great mechanic in Whangarei, New Zealand. He came recommended by many cruisers, and after a long conversation with him we determined he was our kind of guy. The problem was he was also in high demand because he was so good. While still in Vanuatu, we booked him and talked about what we wanted. It was simple: We needed an expert to take a hard look at the engine, diagnose any issues and give us an expert’s opinion on the overall condition of the beast. Then we would decide what should be repaired or if it needed to be rebuilt … or, worst-case scenario, if we would have to dig into the cruising fund for a new main engine.

The check-up

We arrived in Whangarei and our mechanic was as good as recommended. He had done research on our particular engine and was ready to get dirty and take a look. The first test was to start the engine cold. The engine hadn’t been used at this point for several weeks. Before Tim started, he installed a mechanical oil pressure gauge so he could watch the oil pressure. He positioned himself hunched right over the engine for the start so he could see and hear everything. The engine turned over immediately and started; he was checking the oil pressure the entire time. After the engine started, Tim went outside to look at the exhaust, checking for smoke and any oil slick in the water. So far, so good — everything was checking out fine. The engine warmed up and he took heat readings at each cylinder. He knew that they should be relatively consistent with the No. 4 cylinder being slightly hotter than the others. If the temperatures were all over the board, it meant that they were combusting at different levels.

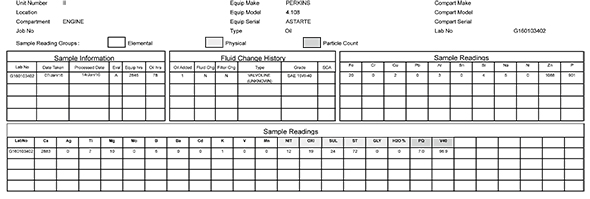

He also took an oil sample and sent it in to a service for analysis. We had always heard that oil analysis was only good if you had it done regularly so you could track any changes in your particular engine. Tim told us that these companies now have such large databases that they have the ability to analyze oil for the various engines without track records. We just had to let him know how many hours since the last oil change and what brand of oil we had, since each manufacturer uses different additives. We referred to this test as the “blood test.”

Michael believed that there was still diesel oil getting into the crankcase. Tim said he didn’t see or smell any, but the oil analysis would tell us for certain. He was a big advocate of the oil test and told us stories about what various analyses had discovered in some of the larger fishing boats he worked on regularly. He also liked that it was an uninvolved third party doing the analysis, so there was no vested interest in the result. The cost of this was $65 NZD (approximately $50 USD at the time).

The results

After a week wait, the oil test results were in. We got an “A.” The oil test is graded with a letter much like school grades. An “A” is the top grade and is good, while a “C” is bad and usually means at least a rebuild. The test answered several of our ongoing questions. We had no diesel in the oil — that was a relief. We also had no other indicators of excessive metal wear or water in the oil. No high-sulfur content also meant that there was not too much exhaust getting into the crankcase.

|

|

The oil sample results gave the engine an “A” rating. |

While we had our mechanic, we did a few additional fixes like a better alignment of the alternator, which required a new bracket. We had the alternator (and backup alternator) cleaned and checked out. It needed a good cleaning because it wasn’t aligned perfectly and there was a plethora of black dust from the belts. New hoses were put on everywhere and a new thermostat was installed in addition to a permanent mechanical oil pressure gauge. Tim suggested that the engine thermostat should be changed every two years as part of a normal maintenance routine. Ours, he said, was “well past the ‘use by’ date!” Michael did most of this work — getting the hoses and thermostat and installing them. Tim adjusted the valves and it turned out they were not in bad shape. He indicated this also meant that things inside the engine were working well, otherwise they would have been more out of adjustment.

All the indicators seemed to show that our Perkins was in pretty good health. Tim’s line was, “You should get another 10,000 hours out of this engine.” We know there are no guarantees that it won’t blow up next month, but what this process did was restore our confidence in the engine. We improved things and did some good maintenance on the old beast.

The total cost was $1,826 NZD, or about $1,225 USD. This included the cost of the mechanic, oil test and parts — the hoses, thermometer, oil pressure meter, alternator checks, bracket and miscellaneous bits. This was in addition to the sweat equity and aches and pains that Michael incurred in the process. All in all, not a bad price for restored confidence!

Barbara Sobocinski and Michael Hawkins have been cruising full time since February 2009. They untied from their dock in St. Petersburg, Fla., and made their Pacific Passage in 2012. Now they are sailing around in the western South Pacific and New Zealand. Their Moody 422, Astarte, is their home. Prior to undoing the dock lines, they both worked in the television business.