Had I known, I would have asked more questions of my family before making my first ocean passage and experiencing seasickness along with the powerful medication often used to combat it.

I didn’t ask because I was young and knew all there was to know; besides, I would never have guessed to inquire if there was any history of congenital seasickness. In my defense, there was — until I chose to misspend my youth schoonering about — virtually no maritime history among my antecedents. My grandparents arrived in steerage from Poland and Lithuania in the early 1900s and prior to that one boat trip had, as far as I know, never been on a boat of any kind.

My father, who I’m told professed a desire to join the merchant marine as a young man but never did, made only two boat voyages. The first of these month-long trips took him from San Francisco to New Guinea during WWII. The second was a return trip a few years later. He informed me many years after that on both passages he was incapacitated for almost the whole journey. So, I must have inherited my weak stomach and unbalanced inner ear from my gene pool.

My first ocean passage, which changed my life forever, was a long stormy trip from Florida through the Turks and Caicos, culminating at St. Thomas. I was as unprepared for my bouts of seasickness as a rube would be on his first visit to a big city. No sooner had we cleared land when the bouncing, swelling, swirling sea waves had me gasping for air, rushing to the rail, where I remained — at least it seems — for the better part of three days. A dog shouldn’t be so sick.

The more experienced crew, about as sympathetic as jailers to their charges, happily ate their meals in full view, always offering some of their food, knowing full well I would wretchedly demur. I secretly wished them all a most hideous demise. Slowly, though, I did begin to recover, and once doing so, my memory of discomfort lapsed, the rest of the passage a grand adventure. But I took note, and on my next voyage began employing an army of medications, some natural, some not, to ward off the dreaded mal de mer.

|

|

Wikipedia |

I began traveling with Dramamine, Bonime, ginger pills, wristbands, ginger cookies and a complete knowledge of acupressure. I tried them all, but nothing did the trick. That is, until my sympathetic doctor wrote me a prescription for scopolamine, applied with a transdermal patch t o the protrusion of the mastoid bone behind the ear. The patches were revolutionary, though they did have some very strange side effects — dry mouth was forewarned in the accompanying literature, as was the possibility of hallucinations.

One of the warnings in the literature is that use of scopolamine “can precipitate psychotic disorders” (conditions that cause difficulty in telling the difference between things or ideas that are real and things or ideas that are not real). Being a product of the 1960s, I was already familiar with hallucinations, so that held no fear for me. I was more concerned about the dry mouth.

I’m not diminishing the potential problems that the drug could cause, nor making light of the dangers involved; but for me, the use of scopolamine saved my sailing career, transforming me from a shaky-legged, green sailor into a competent seaman.

As for the hallucinations, sometimes I remember listening to the conversations of the dolphins, other times to the mysterious celestial objects drifting in the night sky. Weird, I will admit, but not unsettling.

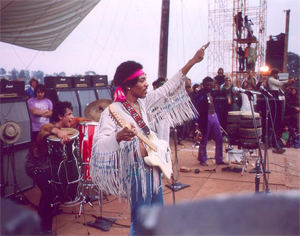

There were other times when my brain’s distorted hard drive transported me back to the be-ins in Central Park or to the Woodstock music festival, where I actually never got to hear any music, stuck in traffic as I was.

So, when I go to sea, a transdermal patch is in place. Perhaps a placebo would work just as well, but why chance it? I am comfortable, impervious to the rolling, pitching and yawing of a sailboat’s motion, with the soundtrack of Jimi Hendrix, conversational dolphins and talkative stars. What could be better?