To the editor: In December 2014 a centuries-old plan to dig a 173-mile trench from the Caribbean to the Pacific, connecting Central America’s largest lake in between, began in earnest. Almost everyone has said it cannot be done but the fact is that, as of this writing, trucks and giant earthmovers are tearing into the ground, widening access roads and leveling hills. In addition to shortening the distance between the Atlantic and Pacific for commercial vessels, a new canal will also assist voyagers as well.

The Gran Canal de Nicaragua (GCN) is a collaboration between the Chinese development company Hong Kong Nicaragua Canal Development Group (HKND) and the Nicaraguan government. The deal resembles many civil infrastructure efforts that Chinese companies are deploying throughout the developing world: a local government approves a massive public-works project and offers absolute autonomy to the company in exchange for vague assurances of future prosperity. The South China Morning Post reported last year that the project would bring 200,000 jobs, while another report predicted only 50,000 jobs. The structure of this deal is simple: HKND builds the Canal, gains a 50-year exclusive management contract, keeps all income from ship traffic, enjoys legal immunity and therefore cannot be sued, has the power of eminent domain to take land, and pays no tax. HKND can extend this deal another 50 years at its discretion. Nicaragua, meanwhile, relinquishes its sovereign immunity and yet is contractually obligated to abate any pollution that results.

The contract was debated for three days in Nicaragua’s legislature. Since called the “costliest boondoggle” and a “giveaway” by the press, including The New York Times, National Geographic and the Associated Press, and decried for its “lack of transparency” by Wired magazine and almost every local observer, the GCN nonetheless appears to be moving ahead.

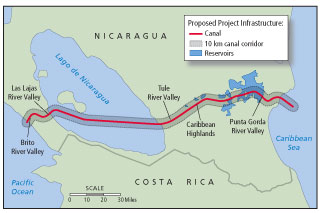

From the east, the GCN will trace its path to Lake Nicaragua from the Caribbean along the San Juan River, which is known locally as “the drain” since it empties the lake’s fresh water into the Caribbean. The 119-mile river has been navigable for centuries, although not of the scale that the GCN will require. From the source of the San Juan, the GCN route calls for a massive east-west dredging project across the southern end of Lake Nicaragua. The lake in this area is only a few feet deep in many places; therefore, the canal will require dredging since the plan calls for a charted depth of up to 98 feet and a width of between 274 and 1,700 feet, depending on the location. Once ships reach the western edge of the Lake, the canal will cross the 30 miles through what is now rural farmland with a few rolling hills. This stretch will involve wholesale removal of earth by the largest Terex diggers on the planet. The eventual route will be three times longer than the Panama Canal but will shave 500 miles off the trip from Los Angeles to New York.

|

|

The planned route of the canal. |

|

Pat Rossi/Navigator Publishing |

With my 11-year-old son Oakley, I set out one morning this past winter from Playa Gigante, a small fishing village on the Pacific near where the canal will meet the ocean, to see for ourselves the emerging project. The motorbike was a 100-cc Kawasaki that shuddered in the crosswinds and labored on the hills. With Oakley on the back, I needed to anticipate the hills and get a running start, downshifting into third gear to crest each one, shifting up to fourth on the descent. The road from Gigante wends inland for a few miles along a rock-strewn, rutted washboard before meeting a smoothly-paved, two-lane country highway — the Nicaraguan equivalent of a Vermont country road with a top speed of about 40 mph. Coming around a bend, we initially missed the turn toward the digging site, a sharp corner in the road with a small sign indicating the town of Miramar (Sea View) to the right. Doubling back, we soon were on a dirt track again, the motorbike’s front tire jittering in every rut. It was a Sunday, which meant there was no activity. Along the two-mile road were signs of recent digging: piles of earth, a few brown construction signs bearing “GCN” superimposed on a map of Nicaragua, and a handful of idle earthmoving machines parked along the side of the road. The road soon ended in a T, and that was it. I stopped the bike, and Oakley jumped off and snapped a picture of me looking puzzled. A young man on a motocross bike soon roared to a stop at the intersection and smiled at us. I asked him where the canal was.

He smiled wanly and held up a hand, indicating around us. “Aqui.”

A few cows grazed in a meadow opposite. The only sound was the dry wind in the trees. To the east, back toward the lake roughly 20 miles away, a few scrubby hills blocked the view; the same was to the west, where an almost-dry riverbed trickled toward the sea some 10 miles away. This was the extent of the GCN I had been reading about.

Everyone I asked about the deal had the same response: resignation tinged with a bland observation about how they expect it will affect their lives. In an area where poverty has been a way of life for as long as anyone can remember, it is as hard to hope for improvement as it is to challenge the combined forces of government and big business.

The following day we were up before dawn, rolling the panga Eunice toward the surf across the sand using a pair of logs. Soon we were waist-deep in the surf, holding the hull steady as the captain and mate positioned a 90-hp Yamaha onto the transom and the hull was buffeted by waves. We had a few seconds to drive the boat further into the surf and tumble in while, moments later, the shaft could be lowered and the prop engaged — all between sets of breakers that could catch us sideways or flip us end over end. It was a well-rehearsed and skillful maneuver that the men appeared to do effortlessly and with grace, jeering and laughing when someone caught a wave in the face or tumbled awkwardly into the bilge (as I did).

That morning, as the sun rose over the dry hills, we pulled up net after net, plucking king mackerel, red snapper and the occasional lion fish, puffer and electric eel, from the gill nets. To the south, the bluffs of Costa Rica appeared a hazy green. The Pacific swells rolled beneath us. Surfers were popping through the waves from the beaches. A few miles to the south, the beach of Brito was where in the next few years the Chinese would be building a “free-trade zone” resort and digging a trench for 18,000-TEU containerships.

|

|

Twain Braden’s son Oakley alongside a beach-launched fishing boat in the town of Gigante. |

|

Twain Braden |

My host shrugged when asked about the GCN, saying it would be bad for fishing. The dredging will churn up so much silt as to make it all but impossible to fish these waters where no one ever sets nets more than a mile or so from the beach. Will the fish come back? No one knows.

Several Nicaraguans have spoken out against the project and its potential destruction of the natural and cultural environment, pollution of the fresh water of the lake, which is the largest supply of drinking water in Central America. Others have complained about the disruption of migratory routes of jaguars and monkeys and others that depend on unfettered corridors for daily and seasonal migration. Also, indigenous villages will lose access to fishing in the lake and game in the surrounding forests.

“The canal could create an environmental disaster in Nicaragua and beyond,” said Jorge A. Huete-Perez, a molecular biologist at University of Central America in Managua. “The excavation of hundreds of kilometers from coast to coast, traversing Lake Nicaragua, the largest drinking-water reservoir in the region, will destroy around 400,000 hectares of rainforest and wetlands.”

To the north, the second largest rainforest in the Western Hemisphere, the Bosawas Biosphere Reserve, contains 2 million hectares of tropical forest and is home to innumerable disappearing species. Turtle nesting sites and coral reefs will simply be bulldozed; rivers dammed; villages of Garifuna, Mayaugua, Miskitu, Rana and Uliva will be evacuated. The freshwater ecosystem of the Lake will be exposed to the salinity of the sea and its ballast-born microspecies.

President Daniel Ortega promises that the GCN will “eradicate poverty” in Nicaragua. But no one has taken the time to contemplate the significant economic, environmental and cultural consequences that such a project will entail. In the meantime, Panama recently began constructing ever-larger locks to keep apace with the increasing size of ships. This relatively modest expansion project will be completed long before the GCN sails its first ship.

—Twain Braden is an admiralty lawyer based in Portland, Maine, and the author of several books, including In Peril and Ghosts of the Pioneers.