I have heard the following quote many times from those who voyage in the Atlantic: “The Gulf Stream makes its own weather.” There is some truth to this statement in a couple of different ways.

The Gulf Stream is part of a large clockwise circulation of surface water in the Atlantic, which is called a subtropical gyre. Gyres like this one are also present in the South Atlantic, the North and South Pacific, and the South Indian Ocean. The gyres in the Southern Hemisphere circulate in a counter-clockwise fashion. Each gyre consists of four parts: a westward flowing equatorial current, an eastward flowing mid-latitude current, a cold eastern boundary current flowing toward the equator on the gyre’s east flank, and a warm western boundary current flowing away from the equator on the west flank of the gyre. The western boundary current is the strongest current in the gyre. The Gulf Stream is a warm western boundary current.

Knowledge of the Gulf Stream has been around for a long time. It was first described in print by Benjamin Franklin who noticed that his passages from America to Europe didn’t take as long as the return trips did. He also noticed the warmer water in the Gulf Stream, and produced a map which today would be considered rather crude, but still captured the essence of the Gulf Stream reasonably well. Today, with much more sophisticated methods available to measure sea surface temperatures, and also to detect slight differences in sea level height, it is possible to map the Gulf Stream with much more precision, pinpointing its meanders and associated eddies and keeping track of how they change with time.

Because the Gulf Stream contains water that is significantly warmer than the surrounding water, it has an effect on the atmosphere right above it. In particular, by adding heat to the lower levels of the atmosphere, the atmosphere becomes more unstable, which allows greater vertical atmospheric motion. This can have a couple of different impacts. First, if there is enough water vapor in the atmosphere, and if the mid and upper levels of the atmosphere are unstable, then the vertical (upward) motions which are initiated by the Gulf Stream in the lower levels of the atmosphere can be carried to higher levels, and this deep upward motion will produce showers and thundershowers. Many mariners have experienced a situation where fair weather prevails in the water around the Gulf Stream, but showers and thundershowers are present over the stream, and this is the reason. Also, when a cold front is approaching and crossing the stream, and the front is generating its own showers and thundershowers, often the activity will become more intense as the front taps into the added instability generated by the warmth of the Gulf Stream.

|

|

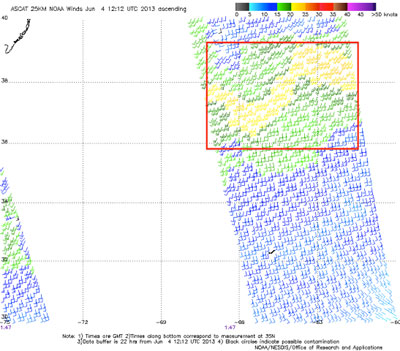

Figure 2 |

The extra instability generated by the warmth of the Gulf Stream can also have more subtle effects even when there are no major weather features nearby, and when there is not “deep” atmospheric instability (i.e. no instability at middle and upper levels). In these situations, the low level instability generated by the warm current will produce smaller scale upward and downward motions. The downward motions will transport higher wind speeds which exist a short distance off the surface and drive them down toward the surface. This situation existed a couple of weeks ago, and is beautifully illustrated by the two attached figures.

Figure 1 is a surface analysis chart for 0000 GMT June 4, 2013. Note the region shown roughly by the red rectangle. This area was on the northwest side of a strong subtropical high, and the orientation and spacing of the isobars indicates winds generally from the SSW in this region at moderate speeds, generally in the 15- to 20-knot range. There are no ship wind reports within the rectangle, but there are some nearby which support this estimate. Also note that there are no fronts near the rectangle at this particular time.

Figure 2 is output from the ASCAT wind observing instrument which rides aboard a polar orbiting satellite taken at about the same time as the chart in Figure 1. The instrument on this satellite works by sensing the roughness of the ocean surface with a radar beam, and is then able to convert the radar return data into wind speed and direction for the region observed. Because the satellite is in a fairly low orbit, it can only observe narrow slices of the Earth at one time. The wind information is shown as traditional wind barbs and feathers, and also color-coded for wind velocity. I have added a red rectangle that is in roughly the same position as the one in Figure 1.

Looking at this figure, the position of the Gulf Stream is very obvious, indicated by the stronger wind speeds. Referring back to the surface chart in Figure 1, there is no reason from the data shown on that chart to expect stronger winds in one area or another within the red rectangle. But the warmer water over the Gulf Stream is aiding in downward momentum transfer of stronger winds aloft, and the result is wind speeds over the Gulf Stream in the 20- to 25-knot range, compared to 15 to 20 knots in the waters immediately surrounding the Gulf Stream. Truly, an example of the Gulf Stream making its own weather!

So mariners should always be prepared for changes in conditions when crossing the Gulf Stream (or any other warm western boundary current). The situation shown by the two figures on June 4th is not one where conditions will be particularly dangerous, but there are situations where dramatic differences in sea state are observed in the Gulf Stream along with significantly enhanced wind speeds. Those situations will be a topic for another time.