Editor’s note: This is the second of our practical weather stories for this issue’s special section on weather. Here a voyaging couple must decide on when the weather is best for a passage in the South Pacific.

In Tonga with an idyllic season of Pacific cruising behind us, we were watching for a weather window to make the 1,100-mile trip to New Zealand. We warily eyed lows spinning eastward off Australia — southern hemisphere lows spinning clockwise, that is. Timing was everything. Too early in the season meant that potential gales south of 30° S would be at their peak; too late, and we could be chased by an early cyclone above that imaginary line.

Naturally, we weren’t the only sailors eager to get our timing right. A seasoned fleet of international cruisers had gathered in Tonga, all fixated on the figurative beacon of New Zealand shining ahead. After months of relatively carefree tropical sailing, signs of obsessive-compulsive behavior were cropping up in every tanned, weather-beaten face. On beaches, in cafes, on the radio, we scrutinized weather reports and compared notes. For most of us, it promised to be an eight- to 10-day passage, plus or minus a possible stopover in North Minerva Reef, nearly 300 miles out of Tonga. Many crews had signed up for the All Points Rally, an informal event that offered the benefit of pre- and post-passage information sessions as well as social gatherings and general weather advice — all for a price irresistible to any cruiser (namely, free). A number of crews were also plugged into professional weather services based in New Zealand and beyond, faithfully awaiting their sage advice. The question in everyone’s mind was, which window was the window?

|

|

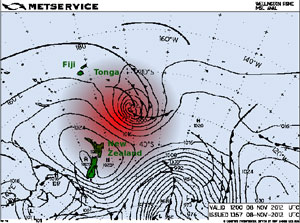

Surface analysis showing a mature low with central pressure 987 hPa with a squash zone against the high to the southwest. |

So when the pros gave the green light for a Thursday through Saturday departure in the first week of November, exactly coinciding with the general time frame of the rally, many cruisers jump-started over the starting line. Some of us, however, waited to see how a mischievous-looking depression forecast to spin off the South Pacific Convergence Zone northwest of Fiji would develop. As the fleet disappeared over the horizon, I couldn’t help but feel slightly … well, wimpy. Were my misgivings a simple case of pre-passage nerves? On the other hand, as a family with a young child, we like to play it safe, especially with any hint of trouble brewing on the horizon. And didn’t John Martin, organizer of the All Points Rally and veteran of 37 Tonga-New Zealand passages, specifically note in an early bulletin: “Keep a good lookout for anything with a closed isobar in the tropic region to your west. If you see one, DON’T leave until it passes or disappears”?

Two days later, our fears were realized as the depression off Fiji materialized and developed into an unmistakably onerous system with the potential to become the first named tropical storm of the season. It was expected to track southeast toward Tonga and the very ocean sector through which the fleet was sailing. Later, it became clear that the depression would inch toward a high-pressure system located over New Zealand, creating an intensified squash zone. In some ways, the general scenario — weather services underestimating a depression forming off Fiji, a high-pressure system over New Zealand creating a squash zone, a cruising rally giving the feeling of a deadline — paralleled that of the infamous 1994 Queen’s Birthday Storm, which claimed seven vessels and three lives.

|

|

A voyaging boat that chose not to move into the protected harbor rides out the storm in the lagoon. |

Soon, it was clear to everyone that the storm spelled trouble. However, theories on how to handle it varied widely. Part of the fleet resolved to stay put in Tonga. Other vessels, already well underway, calculated that they could hasten south, out of the predicted storm track. Still others agonized over backtracking to Tonga. But sailors hate backtracking, especially when the finish line to a long cruising season beckons so seductively. Several outward-bound yachts wavered, turning back for Tonga, then pointing their bows back toward New Zealand after all. A few even made a third course change, about-facing one more time for shelter in Tonga — a wise decision, as events were to prove.

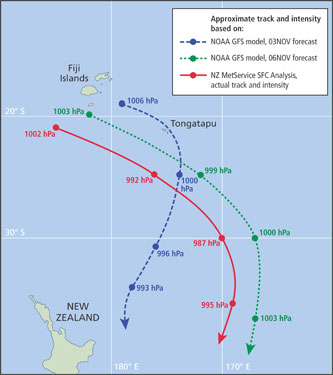

The trouble with racing to beat a storm’s predicted path is that atmospheric forces hold very little regard for human weather forecasts. The low’s expected intensity and track changed from forecast to forecast, playing with the hopes and fears of those underway. What eventually materialized was more serious than the initial warnings had suggested: A more intense low moving further south than expected and closing in on those underway. The idea of speeding south to keep ahead of the storm was complicated by light air conditions during the first days of the passage. That meant immediately relying on engine power — all well and good for large sailboats with big fuel reserves, but smaller vessels with limited capacity had a lot of hopeful calculating to do. Many were forced to burn most of their fossil fuels early on, leaving no plan B for the latter part of the trip, a point when sailboats often motor to reach New Zealand ahead of the next low-pressure system coming across the Tasman Sea. No matter how you packaged it, the scenario was littered with some ugly possibilities.

|

|

A spider web of lines keeps Namani in position as winds peak at 49 knots. |

Meanwhile, back at the ranch…

Those of us who had hung back in Tonga faced a different dilemma: where to seek shelter. Sailors in the Vava’u group had the straightforward choice between several secure anchorages, including Neiafu and Tapana. Down south in Tongatapu, our options were less clear-cut. We were among a dozen boats anchored off Pangaimotu, a small island across the wide lagoon from Nuku’alofa, Tonga’s capital “city.” The holding in sand felt secure, but we were uneasy at the prospect of the open seven-mile fetch to the west — exactly the direction from which 12 hours of high winds were expected at the height of the storm.

The alternative was to move across the bay into the Nuku’alofa harbor, but that required an extensive set-up of two anchors plus lines ashore rigged with rat preventers. Rats — ugh! In the evenings preceding the storm, we all huddled at Big Mama’s open-air restaurant on Pangaimotu to weigh our options. Several crews felt harbor-shy after a recent domino-effect dragging incident back in the central Ha’apai group of Tonga. Better to stay in the open anchorage and allow ourselves space to react, they reasoned, than be squeezed into a corner. Others favored the harbor’s superior shelter and proximity to town. Meanwhile, our children played on the beach, blissfully unencumbered by the anxiety-producing distractions their parents suffered from. The fact that our numbers were swelled by several boats who had turned back from their passages did, however, reassure us that we had made the right decision to stay in Tonga.

With two days remaining before the storm, we opted to move to the inner harbor, going stern-to the breakwater with seven other yachts (and space for several more). The muddy bottom provided excellent holding, and the breadth of the harbor allowed us to get a good 150 feet of chain out on our primary bow anchor. We also set a secondary anchor to the west on another 100 feet of rode. Once settling into a spider web of crisscrossing lines (all sporting discs to discourage stowaway rats), we sat back, watched the barometer drop and crossed our fingers for those at sea.

It’s hard to put a price on safety and comfort, but consider this: One couple who sat out the storm in Tonga forfeited very expensive flights they had already booked from New Zealand. Still, they were relieved to be safe aboard their floating home in relatively sheltered waters. Meanwhile, many yachts that did brave the storm sustained damage and consequently paid for repairs by the oh-so-obliging New Zealand yacht industry. It’s a trade-off that’s difficult to quantify, but certainly bears keeping in mind.

At the height of the storm on Wednesday, the maximum wind speed measured within the harbor was 49 knots, while a boat off Pangaimotu reported a peak of 74 knots. In the harbor, our hulls lay in quiet water, while boats in the anchorage were buffeted by an uncomfortable but harmless two-foot chop. A sharp wind shift had all of us in the harbor leaning hard a-lee, while boats anchored out in the bay were momentarily knocked down, but none the worse for wear (other than cabins in complete disarray). Ultimately, all the vessels in Tongatapu weathered the storm well, whether secured behind the breakwater or anchored out at Pangaimotu.

Drama at sea

The same could not be said of boats at sea. Unfortunately, the storm tracked further west and built larger waves than expected. Consequently, many sailors who thought they would be in safe territory were now directly in the path of the storm or in the squash zone. Most of the fleet on passage reported the likes of 15-foot waves and sustained 40-knot winds — taxing, but not life-threatening. However, the worst of the storm brought 30-foot waves and 50-knot winds. One yacht, Windigo, a 38-foot Beneteau, issued a mayday, reporting injuries and water ingress after being rolled. The nearest vessel, the sturdy 37-foot Tayana Adventure Bound, endured a punishing overnight beat to windward to offer support until a diverted freighter could reach the scene and take the crew of Windigo aboard. In the meantime, an unregistered EPIRB went off roughly 100 miles south of Tonga, setting off more alarms. Later, this was discovered to originate from a fishing boat that had lost power but was able to ride out the storm safely on a drogue.

|

|

Forecast versus actual track and intensity of the tropical depression. Based on NOAA GFS model outputs from Nov. 3 (blue) and Nov. 6 (green), plus NZ MetService surface analysis (red). |

Thankfully, other yachts at sea did not suffer such dramas despite miserable conditions and a number of breakages, from torn sails to broken autopilots and dislodged dinghies, not to mention frayed nerves and general exhaustion. But they were not yet home free. A calm set in after the storm, preceding yet another low sweeping toward New Zealand from Australia. Crews who had already played their fuel joker were forced to sail through the calm at turtle pace, eventually making landfall under another assault of wind, rain and heaving seas. However, most crews were able to view the experience in a positive light, gaining confidence in their vessels and in their abilities to deal with harsh conditions.

A better window

As the storm passed, we in Tonga were relieved that our friends were safe. Now our thoughts could return to our own upcoming passages. As it turned out, we had a much easier ride south. Just as the storm had exhausted many sailors, so too did it suck the energy out of the atmosphere, leaving a harmless series of disorganized high-pressure systems and weak lows floundering in its wake. We were therefore among a second batch of southbound sailors who set off on Nov. 11 with a forecast that promised a slow but hopefully uneventful passage. For us, it was exactly a year to the day that we had left the East Coast for the Caribbean.

This time, the forecast was spot on, and our passage to New Zealand proved to be a calm, even zen-like experience. On our 1981 Dufour 35, Namani, we enjoyed a few fast days, but also set new low-mileage records of 98, 54 and a wallowing 47 miles in successive 24-hour periods. On the other hand, with nothing threatening on the wider horizon, we were content to save diesel, drifting quietly along and counting our blessings. Unlike the boats one system ahead of us, we could put into North Minerva Reef for a one-of-a-kind, mid-ocean anchoring experience, and then resume our passage at an unhurried pace. Eventually, the wind did pick up again, propelling us toward New Zealand’s North Island on a comfortable beam reach.

|

|

Those who left Tonga in the second week of November enjoyed a quiet passage south. |

When we arrived to a sunny week in the Bay of Islands, one of the social organizers of the All Points Rally lamented that we had arrived too late; too late, she meant, for the post-rally events that had been held in Opua. Actually, I thought, we arrived at exactly the right time. Sailing is about bending to the will of the elements, rather than attempting to bend a forecast to one’s will. In fact, many of us are out cruising to escape a world of pressing engagements and an ever-ticking clock. But habits are hard to break, as the story of the first departing fleet demonstrates.

Looking back

In retrospect, we couldn’t help but examine how so many crews found themselves in such a precarious situation at sea. There were a number of contributing factors. First, the difficulty in picking a weather window is that choices can’t be compared ahead of time; you can only weigh the latest forecast against very vague notions of what the future might bring. Consequently, “good enough” is often taken as a reassuring sign. Complicating this was the fact that respected weather routers gave the waiting fleet a thumbs-up to depart. But even experts make mistakes. They and many crews were aware that a depression would form, but gambled with the high odds that the tropical depression would not amount to much (indeed, many forecast lows turn out to be false alarms).

In this case, playing it safe paid off. We benefited from the advice of a locally based amateur weatherman, the veteran of multiple passages between Tonga, Fiji and New Zealand. He was correct in taking a conservative approach, reminding us that the track and intensity of a tropical system is nearly impossible to pinpoint in advance. In other words, trusting computer software that suggests a vessel can stay ahead of a tropical depression’s theoretical track five days hence is a dicey proposition at best, especially in the southwest Pacific. Instead, he heeded his own experience and intuition, and ultimately proved to be spot on.

|

|

Nadine Slavinski and her son Nicky. |

Furthermore, it seems that many crews heeded a natural urge to get moving “on schedule.” The fact that this coincided with the general timing of the rally served to reinforce a dash to the exit door, compounded by subliminal peer pressure. After all, it can be awfully hard to sit still while an anchorage empties out around you! Impatience was another factor, as some crews admitted they were just plum tired of waiting. Picking a weather window really did prove to be an exercise in disciplining oneself to scrutinize the fine print — in both weather forecasts and in expert advice, such as that appearing in John Martin’s early bulletin.

Of course, hindsight is a 20/20 phenomenon. Our observations seek to learn from a trying experience so that we can be all the wiser the next time around. That’s the theory, at least. Since one of the morals of this story is that theory and practice often differ vastly, well … let’s just say we’ll plan for

the worst and hope for the best!

Nadine Slavinski is a parent, sailor, and Harvard-educated teacher. She recently returned from a three year cruise aboard her 35 foot sloop, having sailed from Maine to Australia together with her husband and young son. She is the author of three sailing guides: Pacific Crossing Notes: A Sailor’s Guide to the Coconut Milk Run, Cruising the Caribbean with Kids, and Lesson Plans Ahoy: Hands-On Learning for Sailing Children and Home Schooling Sailors. Her next project is The Silver Spider, a novel of sailing and suspense. See nslavinski.com.