We had a perfect plan for returning WildHorse, our Valiant 42 cutter, to her home port in Watch Hill, R.I., after a winter in the Florida Keys. We took our time moving north in Florida, with even a side trip up the St. Johns River to Jacksonville (a long way, but a beautiful city). But nearing late May it was time to switch to offshore mode and get ready for the 900-nm passage to Rhode Island.

The issue was how to deal with the Gulf Stream. This ocean river is a hot-blooded beast with no conscience. Each encounter with it, no matter how well planned, is like a game of Russian roulette — sometimes you win, sometimes you lose. And when you lose it’s bound to be a mess. The stream does not care.

Luckily I had two fine friends joining me for the voyage, Janet Garnier (“JG”) and Henry DiPietro, both with terrific sailing resumes and both veterans of previous WildHorse voyages. And I had made this exact trip several times before. My confidence was high.

A simple plan

The sail plan was straightforward enough: Sail northeasterly to intersect the Gulf Stream south of Frying Pan Shoals, N.C., and ride it around Cape Lookout and Cape Hatteras and as far north as logic and weather dictate. Then cut for Rhode Island. The speed boost from the stream makes the risk worthwhile, plus the natural wonder of it never fails to captivate the whole crew. Watching the ocean temperature rise into the 80s as speed over the ground follows — first a knot or so, then 2, 3, 4 more knots favorable! The experience never gets old; it is always first-rate excitement.

But the excitement and advantage bear penalties — woe to the mariner caught in the stream with any really bad weather. And even with good weather, only a fool needs to experience the wrath of the stream when a north component wind blows against the north flowing stream. And the worst scenario of all: squally weather with a northeast wind as the Gulf Stream makes its turn to the northeast. This makes that nice, hot water stand straight up into square giant-sized waves that quickly turn excitement into rank, sweaty fear.

|

|

Henry DiPietro, Meisner and Janet Garnier were the crew of WildHorse. |

So with our course laid and sailing strategy made, we departed north Florida on light ENE air, hoping just to sail generally north until the wind consented to a more northeast course to clear Savannah, Charlestown and Cape Fear, then intersecting the stream anywhere the conditions would allow. I never mind light conditions when starting a long trip. It gives captain and crew a chance to get into the rhythm of the sea and boat, and the enjoyment of homemade dinners at sunset on the open ocean is just flat-out wonderful. So we motorsailed happily for the first two days, interspersed with periods of decent sailing.

Unexpected motorsailing

But then the wind went south and light, making apparent air nonexistent. To make any progress, we had to do more motoring. On day three, approaching Cape Fear and Frying Pan Shoals, I began to officially worry about fuel range. All our weather information was in alignment — there was an extended frontal boundary along a line from Nova Scotia to the Chesapeake. North of 38° N was blustery weather and northeast wind. But south of that line, including WildHorse, there was an uncommon lethargy to the weather, with light south wind and very benign sea state — i.e., more motoring. I did some calculations from our consumption record and felt if we could make it to the stream by motorsailing, we could nurse along at very low rpm, letting the Gulf Stream do the work and be left with enough fuel to make port should the wind die at the other end.

Cape Hatteras is the ultimate pinch point. It is the arbiter of all who pass and the study of the weather on approach is intense. What we saw was unusual: a light air, smooth sea rounding was in store. And influencing my decision to go for it was the prospect of an 80-nm roundtrip into Beaufort, N.C., to get fuel, with two days lost and maybe nasty conditions by then at Hatteras keeping us in port.

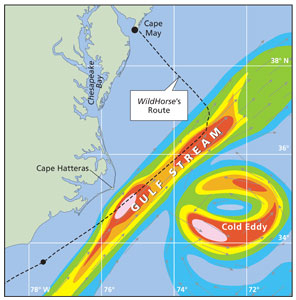

So we made a logical gamble. We would make the stream with enough fuel to employ our strategy, and then let the Gulf Stream do the work as we headed for the Stream’s most northeastern point at 38° N by 071° W, just before it made a big meander to the southeast on its way to the shores of Europe.

|

|

WildHorse at her home port of Watch Hill, R.I. |

WildHorse entered the Gulf Stream southeast of Cape Lookout, at 34° 10’ N by 076° 20’ W. We reduced rpm as the big ocean river pulled us ever faster along its axis. Rounding Cape Hatteras is always an awesome and humbling experience. Rounding in flat seas and light air is downright surrealistic. I should have known right then that there was big trouble ahead.

We proceeded northeast on a course of 60° M, aiming for the exit point 38° N by 071° W, which would leave 190 nm due north for Block Island and home. The stream’s configuration showed a straight-line sail at 60° M would keep WildHorse centered in the stream and the fastest current. And every single weather station I could access, including the professionals (via SSB) confirmed the front would lift and move west, leaving us with easterly air once we exited the stream, promising a close reach in 18 to 22 knots heading for the barn. Piece of cake.

Sudden wind change

At 1300 on Wednesday, June 3, I stood in the companionway staring into the wide eyes of my surprised and worried crew. I did not know what just happened, but I knew life was about to change. I looked over my shoulder and saw what had startled them. The south wind had disappeared and in its place was dead northeast, along with the start of northeast seas. “When the hell did this happen?!” I asked. “Just now, just like that,” came the reply. In the space of this exchange I watched the wind build to 15 knots with suddenly larger seas. We reefed the main and tacked over, rolling out a reefed jib but finding we could only make 90° M course over the ground (COG). So over we tacked, trading the jib for the more closely sheeted staysail, finding the ride smoother and COG around 20° M. But we needed the engine to maintain that course. Not good.

Why was this happening? We were a safe 100-plus nm from our turn point and the frontal boundary at 38° N. Was this transitory? A bleed over from the front? How could all the weather info be wrong? We decided to sail the course we could make good and just be patient and see.

|

|

WildHorse’s route took it into the Gulf Stream before conditions forced seeking refuge at Cape May, N.J. |

We traded tacks and did our best to maintain our strategy, but by 1700 our condition became plain. With mounting wind and steep seas WildHorse was getting clobbered. It was an untenable position and we needed to abandon our 38/071 strategy — and fast. Back at the nav station, I felt the cold grip of anxiety as I realized that our carefully reasoned game plan was in the toilet, worthless. And worse, we had committed ourselves so far north and east that most of our secondary ports were now unreachable. First things first, I thought, we must get out of the stream. And any course to the east was a no-brainer-no-good as it would require fighting the stream’s southeast meander as well as a full crossing of the stream down the line.

We fell off the wind enough to sail fast on starboard to the west and took note of the course made good — 330° M. I drew a vector line along that track and found it split the breakwaters at Cape May, N.J. “We’re going to Cape May,” I shouted with as much confidence I could muster. JG and Henry were quick to agree. But now we had to sail out of the Gulf Stream and across the frontal boundary. I knew it would be nasty all the way to Cape May, some 170 nm, and I told my crew. They did not blink.

Desperate to escape

The stream was now having her way with us and we were desperate to escape. Towering waves had built up in 20-plus knots of northeast air. WildHorse is normally a dry boat, but not now. She got hit hard on the starboard beam by waves the size of boxcars. Green water was arcing up and over our dodger, sometimes missing the whole boat, sometimes just nailing the cockpit. The wind rose with a vengeance and the seas followed, making an awesome, terrible sight. Below was a shambles — and I had put a homemade chicken potpie in the oven. Guess what? No takers. Instead the three of us had a measly, pitiful meal of Matza crackers and peanut butter.

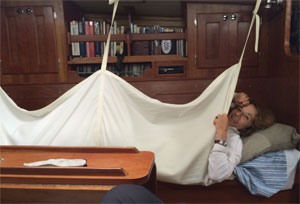

The only thing in our favor was the Gulf Stream’s narrowness at its far northeast point. When we cut and ran I figured two hours at the 8.5 knots we were making would get us close to the western wall. It was two hours of agony, and I swear it was like a living thing had awakened and realized some trespassers had almost gone unpunished. JG had sailed across the Pacific and the Atlantic. She had done the Caribbean and the Panama Canal. But she had never been in the Gulf Stream in northeast air. She did not like it and retired below to her sea berth, which she referred to as “sick bay.”

We hacked and slashed our way, with reefed main and staysail, WildHorse pushing forward in 20-foot breaking seas, doing what she was made to do. And when we reached the edge of the stream, we entered the world of gray we had been planning for days to avoid: the front. The Gulf Stream waves began to lose their monumental force, but we were now in just plain bad weather. Here’s the log from 2200: “Wind up; seas rough; white water everywhere. We are dead on course for Cape May, but gray, windy, menacing conditions prevail. Wind forward of the beam at 25kts. Boat fast and okay; crew not.”

|

|

A still image from a video shot during the height of the rough conditions in the Gulf Stream. |

And for 0000: “Thurs. 5/4 — Crashing, banging, and muscling through wind & waves on course 330M @ 7.5kts; Wx shows no sign of abating; crew just hanging on.”

Then we began to see 25 to 30 knots with stronger gusts, all just forward of the beam. The concussion of WildHorse hitting the walls of water sounded like cannon fire. There was virtually no visibility and we knew we must pass the busy mouth of Delaware Bay to reach Cape May. We expected big traffic but even as dawn broke we could see nothing. Radar and AIS revealed some big boys who did not answer our calls and caused mounting anxiety. But what I was most worried about was seeing the stone jetties at Cape May. An easy entrance, I’d heard, but I’d never been there before.

By mid-morning we were as spent as a crew can be but still had an ETA of 1730, which seemed like a long time to go with no let up. Here’s the log: “1630 — On approach — absolutely nothing visible; no land mass, nothing. Only 7nm off, nothing but gray & white spume. Wind now topping out at 30kts. Cannot get too close with no visual.”

1700: “We see hazy land, all gray monocolor; some tall tanks; no evidence of a stone breachway, nor the major mark, R”CM.” We are fast, fast and should reduce sail, but need power for the seas.”

|

|

JG in her lee-cloth-equipped “sick bay.” |

What about the jetties?

My mind was now racing with nervous energy. How were we going to land the boat? What if we never got a visual of the stone jetties? Would I have enough faith to shoot the breachway on electronics alone? Bailing out at this speed and no visibility was not so simple. I decided on a compromise: We would abort if we got within 1 nm of the entrance without seeing a mark. We would strike the staysail and bear off with just the main along with an engine assist. From downwind of the entrance we would tack and head back for a second try. I had no other plan.

Posting Henry and JG as lookouts keyed to the range and bearing of the jetties, I took the helm. We were just 2 nm off when suddenly, out of the mist and spume, emerged R”CM,” the safe water buoy that aligns with the entrance, only 1 nm beyond. But we still had no visual on the jetties. “Let’s strike the staysail,” I yelled to JG and Henry and they did so quickly. As I started the engine I heard JG exclaim, “There!”

Through the mist came the scratchy indication of dark shapes in the water extending ahead of us. A stone jetty for sure, but which one? We could make out a tall mark but it was colorless in the conditions. Closer, closer and finally just at the point of no return came the second jetty, smaller and with just a single small green can as its marker. “We have them! We’re going in.”

There was an ominous line of white water just inside the jetties that seethed with turbulence. We trimmed the main and applied full throttle and WildHorse blasted through. We were in. The seas abated, the boat righted and for the first time we knew we were clear. We rejoiced.

|

|

Janet Garnier celebrates WildHorse’s Cape May landing. |

With WildHorse safely docked and the crew still limp with emotional exhaustion, I turned to the next most important matter. “What can I get you to drink?” Henry did not hesitate. “Jack Daniel’s Manhattan, light on the vermouth and skip the cherry.” I laughed and said that sounded good to me.

I looked at JG who said, “Make it three, boys.”

If you are really out there, all sailors know there is always risk, especially when weather misbehaves — and if you can count on anything, it is that the weather will not do what it’s supposed to do. If you are in the Gulf Stream (or some other notorious ocean waters) and determined to have it all, you have doubled down and must accept your fate if you happen to roll snake eyes.

The key question: Was the risk worth the potential gain? The answer can only come from the individual mariner.

I’d say I feel a strong affinity for the majestic power and beauty of the Gulf Stream, and to harness this natural wonder and ride it to personal advantage is one of life’s most satisfying adventures. Risk accepted.

Rick Meisner is a former executive who sails his Valiant 42, WildHorse out of Watch Hill, R.I. He has captained WildHorse in several Newport-Bermuda and Marblehead-Halifax ocean races and has cruised WildHorse from Nova Scotia to the Eastern Caribbean and beyond.