Pop, pop, pop … POP! The sound of four fingers separated from a hand while a sailor was snubbing a cruising sailboat to a stop on a pier in the Great Lakes. The same description was given by a recent rodeo participant in Denver as his thumb became trapped between the saddle horn and the rope, with the horse on one end and a cow on the other. Fortunately for both hands, sophisticated medical care was relatively close. Detached fingers are sometimes reattached — sometimes successfully — but they never work quite as well as in the original configuration.

So, first, let’s cover the safety talk. You all know this, but it gets repeated anyway: Be exceedingly careful about where you put your hands. Caution like this should be instinctual for most humans. It is said that we have evolved alongside fire and predators and it is in our DNA to fear them without actually having to think about it. Boats and machinery, however, came along too late to enjoy this evolutionary protection. You have to consciously insert that extra second or two of judgment and experience to make up for where instinct will fail you.

Avoiding finger injury

Boats, like horses and cows, offer an almost unlimited opportunity for personal injury. A few simple habits can help you mitigate some of the risk to an extremely important and vulnerable part of your anatomy:

1. Actually THINK about where you are putting your hands. Force yourself to be slower, more deliberate and more thoughtful in high-risk situations. Remember that risk is a function of probability and consequence. The probability of an adverse event may be no greater offshore than on the bay, but the consequences are far more significant.

|

|

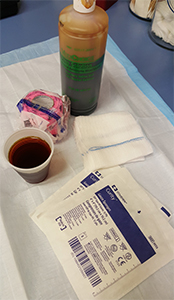

Materials for dressing open wounds: dilute povidone-iodine solution, sterile gauze, non-sterile gauze and bandage-like vet wrap. |

|

Jeff Isaac |

2. Anticipate instability, even alongside the dock. Position and brace yourself so that sudden pitch and roll will not cause a reflex reach to the alternator drive belt to catch your fall. Yes, your boat really is out to get you. A healthy paranoia saves fingers and lives.

3. If you wear gloves, be sure that they fit well — no extra material at the fingertips, no unsecured straps or buckles hanging off the wrist. The same goes for long sleeves on shirts and jackets. These can suck your hand into a drive shaft or windlass in a heartbeat. Never wear a ring or bracelet aboard a boat.

4. Don’t hold a coil of line in your hand if it can come under significant tension. Examples include jib sheets, anchor rode and snubbing line. Flake the line across your palm or on deck instead. Horse people never coil a lead rope in the hand for the same reason.

5. If it will eat fingers and can be fixed, fix it now. This means the belt guard, the sticky windlass switch and the cockpit locker’s broken hold-it-open strap.

6. Let it go. In a serious tug of war, the boat will win. The temporary humiliation of a flogging headsail or a lost anchor is better than counting your fingers at the end of the day and coming up short.

|

|

Xeroform is a longer-lasting open wound dressing. |

|

Jeff Isaac |

If safety fails, fingers can be separated from the owner in a variety of ways. They can be ripped off, as is typical of rotating shaft injuries. Sometimes a long string of tendon accompanies the finger, having been avulsed from the muscle in the forearm. Fingers can be crushed off between a line under load and the drum of the winch. Or, they can be cut off cleanly by the cockpit locker or the blade of a knife or propeller.

If you are still tied to the dock, the plan is straightforward. Bandage the stumps, elevate and apply pressure to stop the bleeding. Call an ambulance. Find the fingers, rinse them off with clean water, wrap them in moist gauze or a towel and put them in a plastic bag to go with the patient.

If you happen to be underway halfway between Panama and the Marquesas, the treatment is still pretty straightforward. Reattachment of the lost fingers is not an option. Perform meticulous wound cleaning, remove any obviously dead tissue and start broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Water clean enough to drink is okay for wound irrigation. If you have any question about the quality of your tankage, make a 1 percent povidone-iodine solution for irrigation and for a wet dressing to preserve the stumps. Tissue and bone that is normally moist should be kept moist.

The only good news here is that you cannot bleed to death from a finger amputation. You cannot go into shock from a finger amputation. Elevation and direct pressure will stop the bleeding quickly. The racing heart, fast breathing, fainting, pale skin and other such symptoms are called “acute stress reaction.” It will not kill you. It will pass.

|

|

A collection of wound cleaning instruments, about $6 worth of material. |

|

Jeff Isaac |

Pain control

At some point in the process, you will be reminded about pain control. Calm, deliberate care and good pain control cures acute stress reaction. This would be a good time to use the opioids and benzodiazepines that you’ve been keeping in your lock box for just such an occasion. Start at the lower end of the dose range and work up only if you need to. Aboard a boat at sea, you want a patient who is awake and feels less pain, not a dysfunctional sleeping crewmember who cannot protect him or herself.

For the long haul, change the dressings and rinse the stumps at least daily with clean water or the 1 percent povidone-iodine solution. Continue the antibiotics for as long as you have them or until you reach medical care. If you have good communication, try to determine the best landfall for access to surgical care or to a plane or train that can get you there. Don’t save the amputated fingers. You won’t get anywhere in time to reattach them. The generally accepted limit is 12 hours, with up to 24 hours in really exceptional cases.

If you are offshore still but in range of rescue and evacuation, you have a more difficult decision to make. Rescue at sea is often prolonged and extremely dangerous for both the patient and the rescuers. A mad dash into a strange harbor at night carries its own set of challenges. You now have to balance these considerable risks against the potential benefit of finger reattachment.

Guidelines for seeking care

Every case is unique, but there are some general guidelines that might help with this decision:

1. The best chances for a favorable reattachment are cleanly severed fingers on a young and healthy patient.

|

|

Sterile gauze soaked with dilute povidone-iodine can be used as a first layer over exposed soft tissue and bone. |

|

Jeff Isaac |

2. Fingertips (last joint outward) are seldom reattached except on very young kids.

3. A single severed finger is not usually reattached, except for the thumb. While reanimating a severed finger is often successful, it is rare to achieve more than 50 percent of its original function. It just ends up getting in the way of an otherwise useful hand.

4. Fingers that are torn or crushed off are poor candidates for reattachment. If you see the “catfish sign,” which consists of strings of nerve or tendon hanging from the finger, you know that arteries are stretched and likely damaged beyond repair.

5. Fingers detached from people who smoke are not good candidates for reattachment. If you plan to sever your fingers, you should quit smoking at least six months prior to the accident.

6. Severed fingers are not, by themselves, a life-threatening emergency.

Radio or satphone medical advice from a qualified source can help with your risk/benefit assessment. Be prepared to describe the fingers, the stumps, the mechanism of injury and the general health of the patient. This can give you a better sense for the likely benefit. Consider, also, your own ability to care for the wounds and the patient while short-handing the boat through a rescue or emergency landfall.

Beware of puddle vision: the tendency to focus on the puddle of blood and the patient’s despair to the exclusion of the big picture. Also beware of the laying-on of guilt, the sense of urgency applied from outside the scene by people who do not fully understand the risks that you are weighing. This is the doctor on the radio who tells you that immediate evacuation to the hospital is the only choice. Remember that there are times when doing good basic medical care on board offers a far better risk/benefit profile than some hairball rescue in the middle of the night.

If, after careful consideration, you do plan to evacuate or run for help with the hope of reattachment, the care that you provide in preparation can make a big difference. Clean and dress the stumps as described above. Start antibiotics immediately. Wrap the fingers in a moist towel or gauze and seal them in a plastic bag. In the ideal setting, you would then float that bag in another bag containing ice and water. The ice and water mix keeps the fingers as cold as possible without freezing them. Don’t forget to send the fingers with the patient. You’d be amazed at how often fingers are left behind.

Jeff Isaac, PA-C is the curriculum director for Wilderness Medical Associates International and instructor for Offshore Emergency Medicine, an intensive course for cruising sailors, also certified by The Ocean Navigator School of Seamanship. He practices emergency medicine in Crested Butte, Colorado.