As the squall passed, the stars began to appear in the inky night sky. A gentle southerly breeze filled in and replaced the trade winds that had been driving our Mason 33, Carina, rapidly along the rhumb line. “Drat, noserlies!” muttered Leslie. “Maybe it’s time to motor.” After almost 12 days of squalls interrupted by calms with a few delightful hours of easy sailing, we agreed it was time to burn some of our hoarded diesel fuel.

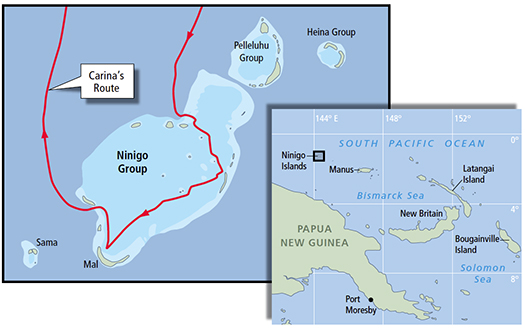

It was 0300 local at 01° S latitude in the lonely western Pacific Ocean and we were on passage from the Republic of Palau, now more than 800 nautical miles behind us. We could just begin to see the signature of the fringing reef of our destination on our radar; the sky was black but dawn was not far away. We were trying to time a mid-morning arrival at the pass in the Ninigo Islands, which would allow us ample daylight for conning and picking our way through to the shallow reefs far into the lagoon to our anchorage. Given the intensity and direction of the wind, motoring was the only option in order to cover the remaining distance and reach our anchorage on time. We furled our headsails and held our breath as we turned the key to the engine, releasing it only when the Yanmar came to life at the push of the starter button.

The rumbling little diesel engine and our anticipation of landfall at a place few visit would keep us both awake, so we set about to make sweet hot tea. We settled into watching our track on a satellite photo displayed on a small tablet since our charts were, at best, inaccurate. With no moon and no swell to create breakers on the reef, there was no room for error as we closed on the atoll. As the eastern sky began to glow, silhouettes of tiny motus emerged on the horizon and we cautiously approached, following the waypoints we had uploaded to our GPS and peering ahead, continuously searching for uncharted hazards, including the unlit sailing canoes known to ply these waters.

|

|

One of the islander’s swift outrigger canoes. |

Through the pass

The pass was only a narrow east-west break in the coral and the rising sun was still low in the sky, so Philip took a bow watch and we pointed Carina at the location indicated on the geo-referenced satellite image. With no tide tables to guide us, we weren’t sure what we might find for current in the pass but hoped for the best — or at least enough wiggle room to abort if necessary. As we entered the pass, Carina began to sashay with the outfalls and small whirlpools and our speed dropped to about 2 knots. Leslie increased the engine rpm and we kept pushing stubbornly against the tidal flow until we emerged inside the lagoon, negotiated shallows and proceeded south, all the while on watch for reefs.

“This is it,” Leslie advised when we had reached the waypoint of our chosen anchorage, and so I let the anchor drop into the bright turquoise water, let Carina drop back and then set the anchor hard. We felt a mixture of exhaustion, elation and disbelief. After months of planning, purchasing and packing hundreds of pounds of supplies and donations, followed by almost two weeks on passage, we had actually arrived at Mal Island in the Ninigo lagoon. And, we had arrived in plenty of time to witness the spectacle of the August racing season of the Seimat outrigger sailing canoes — a culturally rich and highly competitive event dubbed The Great Ninigo Islands Canoe Race.

Almost immediately, an outrigger canoe pushed off the beach to our west, bringing the first of new friends, Michael Tahalam, for a visit aboard. Thus began our idyllic five-week adventure in one of the most remote and friendly cruising destinations we have visited in 13 years of wandering about the Pacific on Carina.

|

|

The Ninigo Islands. |

The magnificent Ninigo Islands, a group of 31 tiny islands set in seven atolls, are part of the Manus Province of Papua New Guinea. These islands, like their distant neighbors of Wuvulu and the Hermit Islands, are seldom visited. During a busy year, only a handful of yachts drop anchor and most of those are friends of those who have already been to Ninigo. We were such a yacht. Not only had friends urged us to sail there, but a few had sent us donations to buy supplies along with gifts, and asked us to carry letters for the families they had learned to love during their own visits. We sailed into Ninigo with humanitarian donations and purchased goods provided by 57 individuals representing 18 yachts and 15 different countries.

Those who cruise here choose to come for many reasons, including the healthy lagoons that make for stunning anchorages set alongside pretty, neat villages. But above all, what is most attractive and endearing — and what brings friends of friends back — are the warm wonderful people and their still-flourishing sailing canoe culture that allows them to sustainably live on little except pluck, hard work and love. That is why we went and that is why we hope someday to go back. If we cannot, we will, like others before us, send back our love through others.

|

|

Leslie with islander Wendy Pihon. |

The Ninigo Islands

The colonial period history of these islands saw various powers claiming ownership and selling the islands and resources to the highest bidder. The first record we found of the sighting of Ninigo was in 1768, though the Spanish “discovered” the Western Islands in 1545. World events periodically changed the players, but the colorful and greedy western entrepreneurs — many who ruled like kings — were all sadly similar. What is more troubling is that, to this day, more than 40 years after PNG independence, the land has not yet been returned to the people who have lived continuously in these islands for thousands of years. The PNG government has asked the cash-poor people for payment for the copra plantations that sit on the islanders’ ancestral lands.

It is remarkable that the culture of the Seimat people survived its occupiers, though in some ways the introduction of genetic material from the outside has made the people stronger. The mixture of genes, from people from the far corners of the world, has certainly helped to make them strong and handsome with fine features and bright eyes.

|

|

Philip receives a colorful hat from islanders. |

Today, only a few hundred generous souls live in the Ninigo group in a handful of remote communities where schools are located. It was only in the past few years that schools have been free, so parents, some of whom are illiterate, are keen to ensure their children are educated. The brightest children can now progress to secondary or tertiary levels of education and find jobs that bring a few kina (PNG currency) back to their families in the villages. Often a family will have a hut near the school and another nearer their historic home or their garden. Most homes are constructed of jungle materials such as pandanus and bamboo.

Converts to Christianity, the villagers are either Roman Catholic or Seventh Day Adventist, though everyone seems to live in harmony and intermarriages occur. Neither denomination in the recent past has sent clergy to support their followers.

The provincial capital, called “town” by the Ninigo people, is Lorengau on Manus Island in the Admiralty group, nearly 200 nautical miles away. The president of the local-level government, a man from the nearby Hermit Islands named Paul Silas, lives there as the sole representative of his people. The deputy president, Kelly Lui, lives in the islands but has no phone service, no email and no boat except for his sailing canoe.

|

|

Some of the structures in Puhipi village. |

What compounds the remoteness of these tiny coral islands is that there are no service boats that call. The last supply boat fell victim to poor maintenance brought on by corruption or poor planning, and was scuttled rather than repaired. Without a regular supply of any commodity that cannot be sourced from the jungle or from the sea, the people treasure simple things like clothing, fishing line, books, food, medicine, pots and pans. With no supply boat, there are also no affordable options for islanders to send even high-value products, such as their pure coconut oil, to market.

There is also no electricity, no refrigeration and no cellphone service. Rain provides drinking water while shallow wells of brackish water provide wash water. Food is gathered each day from the sea or from prolific home gardens scattered throughout the tiny islands. Medical care is poor; malaria, diabetes and untreated injuries take their toll. Dental or eye care is nonexistent, and it seems most adults suffer from poor eyesight from uncorrected vision problems or maladies such as pterygium (surfer’s eye) brought on by excessive exposure to sunlight and irritants.

There is also no industry: The copra plantations of the past are idle, and the few buildings are unkempt or collapsing. A brief contract with an Asian fishing company early in this century badly depleted the fishery and then fell apart, taking dozens of jobs with it, but serendipitously saving the protein source of the people.

|

|

Oscar and Keren fishing aboard their canoe Sea Mate in Ninigo lagoon. |

But despite a myriad of challenges, these friendly, caring and kind people survive and are, for the most part, remarkably healthy and happy. One of the reasons that they can live so well with so little is because they have preserved the tradition of the outrigger sailing canoes that provide transportation, access to fishing grounds and communications links for all. The islanders realize how important the canoes are and dedicate themselves to the preservation of the culture.

The traditional Ninigo canoe

Oscar, our yacht contact, sat with his left leg tucked under him and his right leg swinging fore and aft at the helmsman seat of Sea Mate, his new 9-meter Ninigo canoe. Sea Mate skimmed across the turquoise lagoon and Oscar held the wide steering paddle with a fist in his right hand. He beamed out his warm gap-toothed smile and made a wide arc with his left arm and boomed, “This is our LIFE!” Oscar’s wife, Keren, gave us a Mona Lisa smirk and raised her left eyebrow ever so slightly, tucked a few curly strands of hair behind her ears, and then continued to lay out fishing line, clearly amused by her husband’s joviality. Indeed, the seascape and sailing have been the life of the people here forever, or at least since the great migration of Lapita people across Oceania that began thousands of years ago. The Ninigo people love their lagoon and they love to sail — and it shows in their smiles.

|

|

A race begins in light air. |

According to scholars, the canted rectangular-boom lugsail/single-outrigger canoe design of this tiny corner of Oceania represents a blending of influences from Micronesia and Indonesia. The single asymmetric hull constructed of planked sides set onto a keel with an ama to windward are similar to features we saw in canoes of the outer islands of Yap. Also similar to the Micronesian tradition is the practice of shunting the Ninigo canoe, which is physically moving the mast and helmsman’s station end-for-end when changing course. From East Asia comes the sail design; rectangular lugsails were characteristic of the proas of the Celebes Sea — though Ninigo canoes longer than 9 meters are often sailed as ketches, with two masts carrying lugsail rigs. We saw evidence of rare fore and aft decks on single-hulled outrigger canoes in eastern Mindanao in the Philippines, an area sharing the culture of Indonesia.

And though the sailing canoes that have been plying these waters for thousands of years have inevitably evolved, the extremely efficient current form of the Ninigo canoe may be a recent phenomenon. No one knows for sure, as there is no written history, but according to Kelly Lui, all of the important design elements common today to the traditional Ninigo canoe were first realized in a canoe named Hamanoman (“amazing” in Seimat) around the time of the colonization of the Ninigos in the late 19th century. With a lineage stretching three generations further back to chiefs who conquered the nearby Hermit Islands, Kelly told us that his great-grandfather Saul built Hamanoman and that the design remains a family secret. Indeed, the Ninigo canoes of each clan vary in subtle ways, but because canoe racing is competitive to near fanaticism, such wisdom is not shared.

|

|

The Ninigo canoes are speedy. Here racers practice at Mal Island. |

It may seem odd at first that the Ninigo people are passionate about racing their canoes. But, as Oscar so enthusiastically stated, the canoes are their life — without them, it is doubtful they would be able to continue to thrive in their islands. The canoes are made mostly from materials collected in the jungle or salvaged from the sea, though copper nails and “canvas” for sails are highly prized, and blue poly tarps have replaced the woven pandanus sails of the past. The canoes are efficient and fast, easily reaching speeds of 12 to 15 knots, and provide cost-free transport in a place where buying, fueling and maintaining a skiff is costly. A man’s very identity is inseparable from his canoe; to race against his neighbors and win, that is the ultimate proof of his skill. And the man whose sons are good sailors can send them far into the lagoon or out to sea to help support the family.

Even the women are competitive. We were treated to lunch by Hanit, aka Sweet Honey, on Pihon Island for a number of days during the races. She and her sisters grumbled that the committee had failed to plan a women’s race, even knowing that the races were of such import that few men would allow a woman on their team. And the women wanted to race!

Though there are many canoe racing committees throughout the island group, and races are scheduled at different times of the year, the premier racing season is August when the southeast trades blow the strongest, bringing “big wind” and racing fever to the people. So this is when we chose to make our visit.

|

|

Michael Tahalam and crew salute Carina in the Ninigo lagoon. |

In 2016, we were the only visitors from outside Ninigo and were treated like royalty. A small part of the reason for that was, because of a snafu or two, government funding for the 2016 races never arrived. When the islanders reluctantly shared this information with us, we proposed to donate all the prizes for all the races from our boatload of supplies – clothing, sunglasses, fishing and rigging gear, copper nails, LED lights, headlamps, solar panels and more — that we had packed aboard. The islanders were enthusiastic about the idea of winning the donations, so 74 canoes signed up to race over five days in two locations. We were thrilled to have been able to help preserve this important cultural event and we encourage anyone with means to visit to do the same. You will consider it an experience of a lifetime.

In 2003, Philip DiNuovo and Leslie Linkkila retired from corporate careers and set sail from Kingston, Wash. on an open-ended voyage aboard Carina, their Mason 33. They have traveled now for 13 years and logged 35,000+ nautical miles. Visit their website, www.sv-carina.org.