Factors that can keep cruisers in port include mariners’ health and weather. As I took air, bus and fast ferry from New York City to Isla Mujeres off Cancun, Mexico, I was unaware that nearly a week would go by before these factors would allow us to set off on our passage to Cienfuegos, Cuba, a destination some 300 miles to the east.

On a blustery but warm Thursday afternoon, Lucy and John Knape (my sister and brother-in-law) met me as I stepped from the speedy Ultramar catamaran on Isla Mujeres, a small Mexican island. The Knapes’ boat, a 44-foot DuFour ketch named Maraki, its unique red hull clearly visible even in the spray, was a wet 10-minute ride away in the inflatable. I was ready to sail, but Lucy announced that although Maraki was provisioned and ready to go, there was no way we were leaving the next day. John had broken a tooth and had an emergency appointment with a dentist on the island.

The Knapes had left the east coast of the U.S. two years before and been slowly making their way southward, clockwise around the Lesser Antilles to South America and then back northward, up along Central America. Two decades earlier, they had taken this same DuFour ketch around the world. Lucy was a nurse as well as a seasoned sailor, but major dental repair was beyond her skill and tools.

|

|

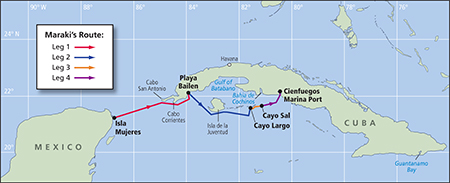

The four legs of the trip from Isla Mujeres to Cienfuegos. |

A bad tooth and lousy weather

“But even without this dental issue, we’re not seeing very favorable conditions for a while,” Lucy said. Sailing from Isla Mujeres to Cienfuegos, Cuba, poses two problems; the first is crossing the northward current of the Gulf Stream as it pours through the Straits of Yucatan in a season known for its northerlies. Current against wind, of course, makes for choppy steep waves. The second problem is that, once protected from the northerlies along the southern coast of Cuba, there are predominant easterly winds combined with a westward current pushing hard against forward motion.

The first item of each morning in our anchorage was the Isla Mujeres Cruisers net, hosted by John of the sailboat Tropical Fun. With his distinct Boston accent, he moderated the broadcast each morning at 0815 on VHF 13. Besides a local weather report, the VHF show offerered a space for priority and emergency traffic, new arrivals’ introductions, departure announcements and a goods/services exchange called “Treasures from the Bilge.” At 0830, the Knapes turned down the VHF volume and switched on the SSB for Chris Parker’s Marine Weather Center for more comprehensive weather information forecast for certain specific parts of the Caribbean. Cruisers who pay a fee to Chris Parker can call in to receive vessel-specific weather and routing advice. John called in, and Chris advised against the crossing for the next few days. “Isla Mujeres will be rough in the anchorage, but the Straits will be much worse,” Chris said.

Before the predicted winds increased to 18 to 25 knots with possible gusts up to 34, we set out a second anchor. The bottom here was muddy and the anchored sailboats — all in the 36- to 55-foot range — were vulnerable to winds from the north. Later that day, two boats did drag anchor, but their crews were able to reset them.

|

|

Lucy and John listen to the radio weather before departing Mexico. |

A departure postponement had already been in place because of the dentist and complications. When John went ashore for another morning of dental work, Lucy and I went with him to explore the charms of Isla Mujeres, which translates to “island of women.” The markets there are busy and buildings brightly painted, but the beaches were empty with the cool (65° F) winds from the north, part of the same huge weather system that dumped snow along the northeastern coast of the U.S.

By Wednesday, day six in Isla Mujeres, the dental work was done. Chris Parker gave a moderately optimistic advisory, provided that we left port that day and entered the lee of Cuba’s western tip before the next round of northerlies returned with a vengeance by Friday. Specifically, he said Wednesday afternoon would see “winds from the SSW 18 to 20 knots diminishing to S 12 at sunset, with the possibility of some squalls. Thursday morning will bring WSW 12 freshening to 15 late and then going NW during the night with 20 to 25 with gusts up to 30.” By then, we planned to be in the east of Cabo San Antonio and in the lee. “Friday will bring NNW going N under 20; Saturday N 20 to 25 around Cayo Largo, going SE 10 for Sunday.” The boats in the anchorage had seen this pattern repeat itself for a month now, and although the crossing might be rough, Maraki and the Knapes could handle it.

With the final decision made to depart, all that remained was a trip ashore to get clearance from the Captain of the Port and a stamp from the passport office. We were at the Port Captain’s office before they opened at 1000, but the authorities — although friendly — carried their own sense of priority. It was not until 1330 that we were back at the ketch. We quickly got the inflatable deflated and secured to the foredeck, and the anchor raised and lashed down for the transit.

We logged departure as 1335 and began weaving our way through the channel toward the opening in the reef. At 1345, as he monitored the engine, John noticed a wet exhaust leak in the bilge. Something had occurred during the month-long stay at anchor. Lucy spun the wheel 180 degrees and we re-anchored. A confused neighboring boat radioed to ask what was wrong, and Lucy explained while John removed the clamp to rework a watertight connection.

|

|

Will Van Dorp and John Knape in the cockpit. |

A second departure

At 1630, we left the anchorage again, this time with a dry bilge and no leaks. Lucy steered carefully, watching the chartplotter as John kept watch from the bow until we cleared the reef and shut off the engine. As the island disappeared, we were soon in more than 200 fathoms of water. A few open fishing boats powered by single outboards negotiated the swells more than 15 miles offshore. By early evening, the bottom had dropped to more than 900 fathoms. Our course was set at 81 degrees and after trimming the jib and main several times, we moved at 5-7 knots toward Cuba. An indication of the strong northward 3-knot current of the Gulf Stream was the need to steer 100 degrees to compensate for the powerful current. We needed to sail far enough south of Cabo San Antonio so that we could clear Cabo Corrientes as well.

Somehow Lucy managed to cook a delicious dinner — rice and chicken — but my system was not ready for the sail and I heaved it overboard in several installments, the extra-strength Stugeron notwithstanding. I stayed in the cockpit as John and Lucy alternated watch through the night. We were careful to keep a careful eye on and to dodge the dozen ships we counted on AIS.

First landfall

Around 0800 we made first landfall off Cabo San Antonio, but then the land disappeared again as we crossed Ensenada de Corrientes on our way to Cabo Corrientes. By noon we saw the light at Cabo Frances and we began to motorsail our way into Bahia de Cortés, where we would be protected behind the Sierra del Rosario range. We lost wind altogether in the late afternoon, and motored the last hour and a half into Gulf of Batabano toward Playa Bailén. About a half-mile off, we anchored in 15 feet of water — 160 miles and 26 hours from Isla Mujeres. Although there was little activity visible on shore, we raised a yellow quarantine flag along with the courtesy Cuban flag from the mizzen, since we had not yet officially cleared into Cuba.

|

|

Maraki approaches the Cuban coast in the Gulf of Batabano to anchor off the beach at Playa Bailen. |

Sunrise on Friday brought a clear sky. If the predicted gusts for Thursday night had happened, we didn’t see them off Playa Bailén. After a hearty breakfast, we raised anchor and set a course of 130 degrees to clear Punta Frances, a point near the southwest corner of Isla de la Juventud (Island of Youth). Punta Frances is named not for the saint but rather for the 16th-century French pirate Francois Le Clerc, also known as Jambe de Bois or Peg Leg.

The winds were so light, John decided to set the asymmetrical spinnaker. Enjoying perfect sailing at around 6 knots, we all sat in the cockpit. A skittering of flying fish suggested it might be good fishing. We threw out a line and soon hooked and lost a dorado and a small sailfish, but landed a bonito and barracuda, which we both quickly returned to the 1,000-plus-fathom water.

By sunset on Friday, we brought the spinnaker down as the winds had freshened and shifted to the northeast. And for what seemed like many hours until I was off watch, the 197-foot lighthouse at Carapachibey showed the otherwise completely dark edge of land, which we could follow at only six miles off because the steep underwater cliffs quickly dropped the sea floor to thousands of feet. In our wake, disturbed bioluminescent creatures glowed, mimicking the thousands of stars overhead.

A squall moved in and we reefed the main just before heavy rain began to fall. Because we were on a close port reach, I couldn’t stay in my portside berth even with the leeboard, so a mat wedged between the center bulkhead and starboard berth allowed me to fall into an enclosed space where I slept.

|

|

Catching a fish on Maraki. |

Cuban charts

One of the problems of sailing in Cuban waters today is the question of reliable information. Our chart resources included a GeoCuba Charts Kit, Agirre and Virgintino’s Cuba Cruising Guide and Calder’s Cuba: A Cruising Guide [editor’s note: the NV Charts company also provides an excellent modernized chart catalog for Cuba]. Beside those, there was the cruisers’ scuttlebutt.

In Isla Mujeres, the Knapes had met several cruisers who had recently sailed from east to west along southern Cuba and reported that any boat seeking shelter from weather between the southeast point and Isla de la Juventud would be asked to leave by the Cuban authorities.

By daybreak on Saturday, the wind had picked up again and we steered farther offshore for a flatter ride. The sea bottom below us varied at depths greater than 2,400 fathoms even though we were about 25 miles offshore. By midmorning, we’d decided to drop all sail and motor into Cayo Largo.

About five miles off Cayo Largo, we spotted what at first seemed like a lighthouse, but we soon recognized it was a sailboat — a sloop running downwind, the first we’d seen since leaving Isla Mujeres. We wondered whether it was Ghost Boat, which had inquired on Chris Parker’s show about timing for a passage in the opposite direction of us. Also anchored a mile or so out was Star Flyer, a 366-foot Malta-registered barquentine with the capacity for more than 100 passengers. We found a location inside the reef and anchored in 15 feet of clear blue water over sand. Leg No. 2 of the passage was marked at 150 miles in 32 hours.

|

|

John dousing the asymmetrical. |

With our yellow quarantine flag still flying, we departed Cayo Largo at 1000 on Sunday morning, hoping for an easy 24-mile run to Cayo Sal, which would offer a good anchorage with protection from the forecast 15- to18-knot wind from the east. We motored the first two hours, several times burying the bow of the ketch in the steep waves.

But, by noon we had cleared the southeast point of Cayo Largo and could turn to 35 degrees and into the shallower waters of Banco de los Jardines, protected from the deep waters by a reef. By 1530 we were anchored off Cayo Sal. A Swedish ketch was already there, as was a small Cuban fishing boat. Two men seemed to be stripping a wrecked catamaran on the rocks on the north side of Cayo Sal. Periodically water shot high from a blowhole near there as well, but having not officially entered Cuba, we chose not to go ashore. We snorkeled near the boat and then enjoyed some rum with dinner.

Noise in the anchorage

Before night fell, a catamaran likely out of the charter fleet in Cienfuegos sailed into our anchorage, bringing a fair amount of celebratory noise from its crew. They also ran their inflatable out to a nearby Cuban fishing boat several times, possibly to barter for fresh fish or lobsters. As I mentioned before, we had seen no pleasure boats until Cayo Largo; since then, we’d seen at least a dozen out of the charter fleets in both Cayo Largo and Cienfuegos as well as a few private cruisers. It’s possible to fly directly to the international airport in Cienfuegos and a few hours later sail away on a chartered vessel.

|

|

The lighthouse at Cayo Guano del Este, built in 1970 to look like a Soviet rocket. |

On Monday morning, Feb. 1, we got underway soon after sunrise. An unidentified catamaran followed us in for most of the 50 miles remaining for Cienfuegos. A direct 30-degree course for the entrance to Cienfuegos was not possible because of the prohibited zone across Gulf of Cazones, one bay of which is Bahía de Cochinos, the infamous Bay of Pigs. The story was that this water is prohibited because of dangerous currents and calms. I was happy for the roundabout route because it took us within a half-mile of the lighthouse on Cayo Guano del Este, a light erected in 1970 and designed to look like a Soviet rocket. When we dropped to less than 4 knots due to dying winds, we started up the engine and motorsailed in. Eventually what was a squall line dissipated and showed a ridgeline below it, the Escambray Mountains to the southeast of Cienfuegos.

By 1500, we were several miles off the entrance to the bay. North of the lighthouse, tall buildings — Cienfuegos City, we assumed — were visible over the ridge, and farther away along the beach was the unfinished and all but abandoned Juragua nuclear power plant. Although we feared that the squalls atop the Escambray might dampen an otherwise beautiful last leg and obscure the markers in the four-mile channel up to our anchorage in Cienfuegos, the clouds stayed on the peaks. We met the Panamian bulker Celia at the entrance and passed starboard to starboard, still flying the yellow quarantine flag.

The winding channel turned out to be well marked and deep as well as picturesque with many places beckoning to explore; notably, a modern hotel, an 18th-century fortress and some small fishing villages. We radioed the dockmaster in Cienfuegos requesting to check in with the authorities and got instructions to anchor in front of the yacht club, where they would come out to meet us. Directly ahead were an oil refinery and other commercial docks, but a clutch of cruising boats to starboard was our destination. The catamaran that followed us in turned out to be one the Knapes knew from their Thanksgiving in Grand Cayman. And as we motored through the anchorage there was a Dutch catamaran, Bella Ciao, they knew from cruising in Panama a half-year back. We dropped the hook near Bella Ciao and logged the time as 1630 on Monday, 360 miles total from Isla Mujeres and not quite 75 hours of travel elapsed.

|

|

The harbor at Cienfuegos, with visiting yachts and the ornate yacht club on shore at right. |

Free to go ashore

By 1730, the yellow quarantine flag was down, permitted by a doctor who was ferried out by a friendly dockmaster named Nelson, who spoke English quite well. Later, Nelson returned with three customs and passport control officials dressed in military shirts with epaulettes, equally friendly but professional. The customs officials requested we open a few compartments and then stamped loose forms we were told to keep with our passports, explaining they could stamp our passports if we so desired as well. Finally, with the condition that the inflatable be used only for transit between the anchorage and the shore and that it needed to be raised out of the water each night, we were told we were free to come ashore.

Regardless of all the delays in Isla Mujeres, Tuesday morning we still needed to sign a contract with the marina. Nelson, the dockmaster, told us that rather than go all the way into the town to change money, they also could do this at the Hotel Jagua about a 10-minute walk away. Cuba has two currencies; the Cuban peso is used by Cubans, and the convertible peso or CUC (pronounced “kook”), is used by foreigners. A clerk at Hotel Jagua changed money with a minimum of paperwork or protocol, making me feel one step closer to meeting my schedule. With CUCs in pocket, we set out to explore Cienfuegos. My attention was constantly pulled by the classic American cars.

As we strolled along the malecon, a man on a bicycle stopped and asked if we would need a taxi — a collectivo, or shared taxi — to Havana, almost 150 miles away. We negotiated a price with Juan, he showed an ID (perhaps as a way to establish credibility) and we agreed on a time to meet Wednesday morning. Then Lucy, John, and I walked farther into town to locate the bus terminal as a backup plan.

Come Wednesday morning, Juan showed up at the marina gate as we had agreed. He had even better news: Because he had located two other passengers to share the taxi, my price would be 25 percent less. No catch. That’s how collectivos work. And he had other good news — a contact there who ran a casa particular, a private B&B. I said my goodbyes to John and Lucy, as they didn’t share my travel schedule and had planned to spend their entire month-long Cuba visa sailing slowly around the southern coast of Cuba before making their way to the Bahamas and then to Florida.

By early afternoon the driver dropped me off at a specific address on a narrow street in “Havana Vieja,” the old city, and I had a place to stay — not at the casa particular Juan had suggested because it had no vacancy, but at another one around the corner. There is an extensive network of these lodgings that seem to support each other in this way. I spent 24 fascinating hours in Havana before catching my return flight to the U.S.

William Van Dorp is is a photographer and writer based in New York City. His articles have appeared in various publications, including Professional Mariner magazine.