Editor’s note: In part two of his look at engine room checks, Jeff Merrill discusses the timing and focus of ER visits.

Like all good chores, your ER checks should follow a routine and be consistent. I suggest that you do an inspection every hour at the top of the hour until you become intimately familiar with the sights, sounds and smells in your ER. Of course, someone capable must take the helm and safely navigate so that you can go do your check. With a set of targets (temperature and visual targets to inspect) you now need to learn how to get comfortable going inside this warm confined space. Repetition will help you develop a baseline of what is “normal” so that if something changes (a fuel sight tube is dripping or main engine oil is leaking on the drip pan) you will be able to more quickly identify the problem. Another reason for every hour on the hour — especially when the boat is new to you — is that, in theory, you will be no more than 60 minutes into a problem. So, for example, if you look into the bilge and see a yellow oil that wasn’t there before, and you look over to the active fin stabilizer reservoir and notice that oil level in the tank has dropped well below the blue tape mark you made, you’ll know to quickly go up to the pilothouse to shut down the active fins. This is a classic real-world example of what I saw and how I reacted on a new boat delivery that prevented a much more destructive outcome had the oil run dry.

I’ve found that it takes about a half-dozen inspections to best establish the work flow for recording data, and then I like to number each target location so you can logically follow the numerical trail to log in the information on your spreadsheet.

|

|

A coolant tank marked for proper cold level. |

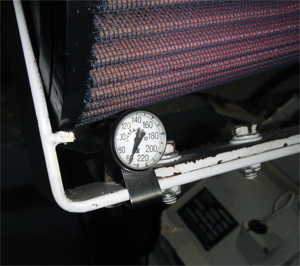

Diesel engines need fuel, electricity, air and cooling. The air filter elements are probably the most commonly overlooked pieces of equipment. You can purchase a simple thermometer gauge that will attach to the filter housing to easily keep track of your true engine room temperature.

Shifting to a longer interval

After you feel more comfortable with your ER and have it “dialed-in,” you can shift to a once-per-watch inspection with an interval of doing an inspection every three or four hours. Even with the longer interval, however, I still like to at least poke my head in every hour for a quick look around when possible. Along this theme, I recommend you have a plan in place for a “quick peek” inspection. Sometimes, especially offshore in rough weather, it is too uncomfortable and borderline unsafe to spend a lot of time in the ER. You should have a priority list to view the essentials in a minimum amount of time. When I do these, I focus on:

• Fuel valves (are the supply and return valves correct?)

• Racor vacuum gauge (normal, not too much vacuum)

• Stuffing box temperature (is it cool and in range?)

• Bilge level (are we taking on water?)

• Engine intake through-hull and strainer (open valve and clear strainer?)

• Air filter temperature gauge

• Quick visual scan of machinery, looking for drips/leaks or anything abnormal

|

|

A thermometer attached to an air filter. |

A quick peek can usually be conducted in less than two minutes; you are only shooting one temperature reading (stuffing box) and the other inspections are all visual.

Before you do your inspection, let the person at the helm know that you are going to the ER. The new helmsperson should try to avoid any sharp turns so that you don’t get jostled about. They may be able to see you via a closed-circuit television (CCTV) monitor in the pilothouse, but you won’t be able to see them (you can make faces and gestures at the camera, but you won’t know if they are watching). I also like to suggest two important tips:

1. When you go into the engine room, close the door behind you. This is not only courteous (less noise and heat coming into the interior) but it is a subtle “telegraphing” location identifier. Even on larger trawlers you are often able to discern the slight change in noise when the ER door is opened and closed — a simple way for the watch stander to keep track of the ER inspector.

2. If you are at the helm, you don’t have an easy way to signal the ER inspector — they have earmuffs on and can’t hear you. You could flash the lights on and off but you might hinder their vision and unintentionally make them stumble. The rule I like to recommend is that if you are in the ER and you don’t like it or feel uncomfortable, get out. If you are in the pilothouse and need the person in the ER to come out, change the rpm. If this is discussed upfront, then you have a simple method of communicating. Most of the time you would throttle back if something was amiss and that is a simple warning to the inspector to come back up to the bridge.

|

|

An absorbent pad can catch drips and let you know where and how much is leaking. |

Rpm is a vessel’s heartbeat

On a long trip, the rpm is stabilized when you are underway and rarely changed. So, when it does change, the crew feels and hears this, and it normally means something has changed and often results in an “all hands on deck” race to the pilothouse. Remember, your engine rpm is your heartbeat and breathing combined; you will settle in to a norm based on sea conditions and distance to your destination.

The pilothouse engine control panels only provide the basics — hours, rpm, voltage, oil pressure and coolant temp — there is a lot more going on and periodic ER checks are essential.

Many trawler owners will wipe down their engines and tidy up the ER before taking off. It will be easier to see leaks, belt dust and other things so you can stay tuned in to your machinery. Line the under-engine pan with absorbent diapers so you can quickly spot fuel or oil leaks. Catching something early on may save a lot of frustration.

Even if you don’t have the mechanical skills to make repairs, by learning more about your ER you will be better able to diagnose minor issues before they become major problems. If you can become attuned to what is normal, you will be able to describe the abnormal symptoms and hopefully have enough background to put a “band-aid” on it or tie a splint until you can get back to shore and bring in the pros.

Jeff Merrill, CPYB, is the president of Jeff Merrill Yacht Sales, Inc.- www.JMYS.com. Jeff is constantly looking for new ideas to improve and simplify the trawler lifestyle. If you have a suggestion or want to get in touch please e-mail Merrill at: Jeff.Merrill@JMYS.com.