To the editor: Despite the obvious danger (Editor’s note: Vanuatu was just hit by cyclone Pam as this issue goes to press), the idea of spending the South Pacific cyclone season in the tropics is tempting. Many of us who cruise in the tropics have a difficult time giving up the barefoot-and-bikini lifestyle to hole up in a sub-tropical region for six months and await our chance to return to tropical paradise. Every year, hundreds of boats transit the South Pacific, leaving from ports in North or Central America. By the end of the cruising season, each boat has to decide where they feel safe to weather out the South Pacific cyclone season. The most common strategy is to reach New Zealand or Australia by the end of October or early November.

While sailors from some countries, notably the French, having been staying year-round in the South Pacific for decades, the idea is catching on with a growing minority of cruisers from other countries. In general these boats take one of three strategies: 1) stay inside the hurricane-affected zone, either moored or cruising near a hurricane hole; 2) take the boat north outside of the cyclone zone; or 3) take the boat east outside of the cyclone-affected zone.

We have spent two seasons in the South Pacific without leaving the tropics, and while researching our options we came across a great deal of seemingly contradictory and misleading information from fellow cruisers, experts and cruising guides. The question of “what is safe enough” is something that must be answered individually.

The two questions I struggled with when planning for two cyclone seasons in the South Pacific are: 1) where, exactly, is “outside of the zone,” and 2) if cruising in the zone or in the gray areas, what is the relative risk of different countries and regions?

Nothing here challenges the conventional wisdom that the safest thing to do for your boat and your body is to stay outside of the cyclone belt during cyclone season. For those who want to take a break from the stress of keeping your eye constantly on the weather, for those who want to have minimal risk and for those whose insurance requires it, going to New Zealand or Australia will continue to be the default option for cyclone season during a South Pacific cruise.

Where are the borders of the cyclone zone?

The question that is most difficult to answer for those planning on taking the boat outside of the cyclone zone is how far north or east do you need to take your vessel to be “safe”? Like many important questions, the initial answer is “it depends.” In this case, it depends on whether the current year is El Nino, La Nina or neutral. While making our own decisions about where to spend hurricane season in the South Pacific, I examined the geographical range of hurricanes in all three types of years.

The answer to this question lies in 36 years of cyclone data from the 1969-70 season to the 2005-06 season compiled by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Using their data, and defining “low risk” as being less than 0.1 cyclones per year — or fewer than one in 10 years — overall we find that cruisers can stay in the low-risk zone during cyclone season by staying east of 147° W or north of 8° S. These numbers are averaged across all years but the risk depends heavily on the ENSO category (i.e., El Nino, La Nina or neutral).

In an El Nino year, the number of cyclones increases, the intensity of cyclones increases and cyclones move further north and further east than in other parts of the ENSO cycle. For that reason, the prudent sailor will use the current ENSO status to refine their risk assessment. During El Nino, the low-risk region shrinks to north of 5° S and east of approximately 128° W (at 20° S), or east of 137° W at 12° S and above. Conversely, in a La Nina year, the low-risk region expands to anywhere north of 10° S and east of 167° W between 10° S and 20° S.

|

|

Livia Gilstrap’s boat Estrellita in the Gambier Islands. |

|

Livia Gilstrap |

The change in cyclone season boundaries based on ENSO status applies mostly to border regions such as French Polynesia, a common hurricane season possibility. The Australian Bureau of Meteorology data show that in both La Nina and ENSO neutral years, almost all of French Polynesia is still in the low-risk zone, although elements are on the border — including parts of the Society and Austral islands. However, in an El Nino year, the Marquesas are the only low-risk area in French Polynesia. Similarly, further west in the Pacific in a La Nina year, countries like Tuvalu are in the low-risk zone but in an El Nino year they are not.

All of the above are probabilistic statements and it only takes one cyclone to ruin someone’s cruise or take someone’s life. Defining “low risk” as fewer than one in 10 years may not be close enough to zero for a given navigator and her crew to feel safe. Thus it is important to know how far east and how far north cyclones have ever traveled.

Exact cyclone records are publicly available from 1969 to 2010 by registering for and downloading the SPEArTC dataset. In that 41-year time period, the furthest points that cyclones reached are as follows:

Farthest east: Cyclone Ursula in 1997-98 traveled farthest east, reaching 110° W at 38° S.

Farthest north: In the western South Pacific, west of 180° E, a number of hurricanes have come as far north as 3° S. The farthest north was in 1982 when Bernie reached 3° 12’ S. The farther west you look, the northernmost reach of cyclones retreats further from the equator. At 180° E, one cyclone reached 4° S (Anne, 1998) while as far east as the Marquesas (139° W) the northernmost cyclone track reached only as far north as 9° S.

Furthest northeast: 1982-83 was the hardest year for French Polynesia on record, as well as the strongest El Nino year on record. That year, a number of cyclone tracks ran surprisingly close to the Marquesas (Cyclones Nano, Veena, Orama, etc.). However, only two of these storms reached cyclone status (greater than 34 knots) near the Marquesas, and none of these cyclones reached hurricane force (greater than 64 knots) until they were in the Tuamotus (Dupon, 1984). Thus, even though numerous tracks run near the Marquesas, no Category 3 tropical cyclones — what would be considered hurricanes on the Saffir-Simpson Scale — have been recorded closer to the Marquesas than the Tuamotus.

The issue of exact boundaries is again impacted by ENSO status and also by timing within the season (i.e., farther reaching later within each hurricane season). For example, in French Polynesia, the main Tuamotus that lie above 20° S have been hit by hurricanes in all ENSO states. However, in La Nina and neutral ENSO years, in the 41 years beginning with the 1969-70 season, the Tuamotus above 20° S have never been hit by a hurricane in the early half of the hurricane season (November through January), only in the late half of the season.

Which countries have a higher risk of cyclones?

Although it is relatively common knowledge that areas of the Western South Pacific have a higher risk than countries to the east, finding concrete estimates of regional risk can be surprisingly difficult.

Here I present the raw data on historical cyclones in various countries so that the navigator can make an informed decision when deciding on what level of risk they are willing to chance.

|

|

A boatyard in Fiji. |

|

Livia Gilstrap |

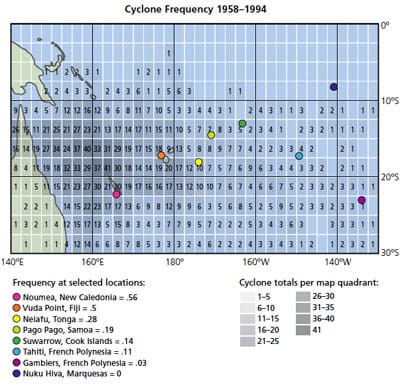

The accompanying graph presents 36 years of cyclone data (Dettmer-Shea, 2008). As is common among agencies tracking cyclones in the South Pacific, the minimum sustained wind speed for a Category 1 cyclone is greater than 34 knots. Each quadrant in the graph represents a section of the ocean that is 2.5 degrees of latitude wide and 2.5 degrees of longitude tall. For quick reference I have marked 8 ports. For each port, I have calculated (on average) over those 36 years the number of cyclones per year that came into the 2.5-degree square quadrant containing the port.

Keep in mind that saying that a cyclone would enter the grid is not the same as saying the port itself would have a direct hit; the eye might have been fairly far away, and the cyclone may have been only a Category 1 cyclone of more than 34 knots.

However, with those caveats the numbers paint a very clear picture of the relative risk of staying in the eight regions. For example, the Noumea quadrant has seen cyclones transit 18 times more often than the Gambiers. The quadrant containing Neiafu has had 2.5 times more cyclones than that of Tahiti.

Of course, it is important to bear in mind a number of additional factors: a storm doesn’t have to be of hurricane strength to cause serious damage; the historical data are good indicators of past activity but climate is changing and there is already evidence that the hurricane seasons might be lengthening; particular care should be taken close to the boundaries of geography and season start and finish; and finally, it only takes one exception to the historical data to destroy property and lives. Whether to consider these options requires careful analysis of many factors including ENSO status, personal risk comfort, insurance requirements and the type and quality of protection in any specific port.

Keeping in mind the risks, the benefits of staying inside the cyclone belt, or on its margins, are numerous — instead of spending six months of every year holed up in the high latitudes, it is possible to continue cruising in wide open anchorages, living in swimsuits and flip-flops and, in some of the areas along the edge of the tropics like the Gambiers, enjoying the warm water and sunshine at the prime season of the year.

—Livia L. Gilstrap is a live-aboard voyager with her partner Carol Dupuis aboard their 35-foot Wauquiez Pretorien, Estrellita 5.10b. Their blog is thegiddyupplan.blogspot.com.