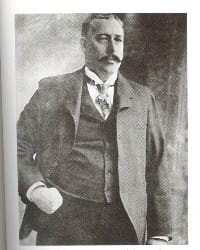

ON178 Anyone familiar with the history of the Gloucester, Mass., fishing fleet has probably heard the name Howard Blackburn. A heroic character, his lifetime compassed the great age of the fishing schooners working off the Grand Banks in search for halibut and the once ubiquitous cod. Great schooners would depart Gloucester in all months of the year bound to the Banks where the fishermen would row off in two-man dories setting long lines of baited hooks. This occupation was fraught with danger. Winter storms would overwhelm them, sometimes they would be run down by passing steamers, and sometimes they’d get separated from their ships and be lost forever on the lonely sea. Some survived and perhaps the greatest survival story belongs to Howard Blackburn.

In the winter of 1883, Blackburn shipped aboard the fishing schooner Grace L. Fears bound for the Burgeo Bank off the coast of Newfoundland in search of halibut. Along with dory mate Tom Welch, they set out from Fears to lay out the long line. The following day with the weather beginning to deteriorate, they went out in the dory to collect their gear. But soon snow fell. They lost sight of the their ship and found themselves buffeted by impossibly cold, blustery winds. For two days they bailed and tried to find their schooner. While bailing Blackburn lost his mittens. Worst of all, Welch died. Made of sterner stuff than we can imagine, Blackburn dipped his hands into the ocean and froze them into position around the oarlocks so that he could continue rowing. It was about 60 miles to the Newfoundland coast and he was determined to make it there alive.

With the body of Welch in the stern sheets, Blackburn rowed for five days until he made the shore. He crawled from the dory, found a small fishing cottage and was saved. He lost all his fingers, except for his thumbs, and most of his toes. Blackburn returned to Gloucester, gave up fishing and opened a bar.

When gold was discovered in Alaska, he put together a mining company, bought a schooner, then sailed around Cape Horn to San Francisco. Blackburn pushed on to Alaska and went broke.

Instead of being beaten by the experience, Blackburn decided to sail single-handed across the Atlantic. In 1899, he had commissioned a 30-foot gaff-rigged cutter patterned after a local fishing boat. He called the boat Great Western and off he went, arriving in England 62 days later. How he was able to handle a gaff–rigged boat, bereft of fingers is a mystery. Even more intriguing is how he was able to use a sextant to get sights.

In the intervening years Blackburn undertook more small boat adventures before dying in Gloucester in 1932.

Let’s go aboard Great Western. It is July 15th and we are approaching Sable Shoals heading east across the Atlantic Ocean. His DR is 42° 50′ N by 58° 30′ W. He is approaching Cape Sable Island and wants to make certain in that fog-bound part of the ocean that he doesn’t get into the shoals that surround the area. His height of eye &mdash Blackburn was a big man &mdash is nine feet above the water. He gets a glimpse of the sun at 1306. At 1606:15 he takes a lower limb shot of the sun with an Hs of 68° 34.3′.

A. What is the Ho?

B. What is the intercept?

C. What is the estimated position (EP)?