Crossing an ocean on paper and on a boat are two vastly different exercises. In the years we spent dreaming about and then planning a Pacific crossing, we spent many an hour pouring over charts, measuring and re-measuring distances, reading books and blogs. Foremost in our minds were the longest passages: 3,000 miles from the Galápagos Islands to the Marquesas, and 1,000 miles from Tonga to New Zealand. In comparison, the western end of the ocean seemed like a piece of cake. Only 500 miles from Fiji to Vanuatu, and a pesky 300 miles from Vanuatu to New Caledonia: mere stepping stones that fall well within the span of a reasonably reliable weather forecast.

But the ocean is not made of paper; it’s a liquid world that shifts and changes with every puff of wind, every change in air pressure. And the southwest Pacific, at least in our experience, is quite a different beast than its distant cousin to the east. Our 1981 Dufour 35, Namani, took it all in stride, as did her crew: myself, my husband Markus, and our 9-year-old son, Nicky. But we learned many a lesson along the way. One of which was that the southwest Pacific can be considered an ocean of its own.

|

Westward bound

Even with a three-year sabbatical, we are always mindful of a ticking clock in our cruising — particularly, the November onset of cyclone season in the Pacific. After two packed months of wonderful Fijian hospitality and scenery, it was time to move on for the last of our island landfalls: fascinating Vanuatu, then New Caledonia. Eventually, we would head on to Australia to sit out cyclone season out of the tropics. Leaving Lautoka at noon one fine August day, we threaded through our last Fijian reef. Namani’s bow pointed west into the setting sun for what would be a four-day passage to the island of Anatom (Aneityum) in southern Vanuatu. We’d long since learned to treat GRIB weather files with a grain of salt, and sure enough, the wind was significantly higher than predicted. With 20 knots of wind from the south, we were humming along at six knots on a rhumb line course of 250°.

|

|

Slavinski at the helm of Namani in the southwest Pacific. |

Nothing to complain about — except for a contrary southwest swell. We knew to expect that, too, but somehow hadn’t quite imagined it being quite so uncomfortable, with regular dousings of our normally dry cockpit for the first 48 hours of the passage. Splish! One wave would try to sneak aboard from the starboard quarter. Splash! The next would bowl us over from port. All hatches remained sealed tight, the cabin a stuffy refuge from the elements. All the crews checking in on our informal SSB net were equally miffed. What happened to the pacific part of the Pacific?

|

|

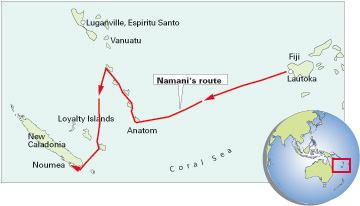

Namani’s route. Though the distances were short, the weather and seas were more challenging than the southeast Pacific. |

It was the short period of the waves that did it, not the size (six to eight feet). Like the Inuit, who have multiple terms for different types of snow, I’m convinced that master Pacific navigators of old had a special name for this kind of swell: something with lots of vowels and a melodic Melanesian sound. My version, however, had just one syllable and four letters. The only way to achieve a more comfortable motion was to fall off the rhumb line by 15°. This is a recurring dilemma aboard Namani: whether to pay our dues early in a passage, or to gamble that we will see easier conditions later. What to do? We gritted our teeth, hung on, and zipped our foul weather jackets tight.

By noon of the next day, the wind was up to 30 knots and we caved in, putting in a third reef and choosing a more comfortable westward heading in squally conditions. The slender arc of a beautiful crescent moon gave us something positive to focus on, its lazy lean a reminder of our latitude at 18° S. Back in Fiji, we had crossed the International Date Line and were now firmly in the realm of east longitude, another reminder of how very, very far we’d come from our starting point in Portland, Maine (70° W, for the record). Another sunny point in those cloudy days was the positive attitude of our son, who’d pop up on deck and declare it “not so bad!” before disappearing into his cozy quarterberth bunk. Back at age 4, when we cruised the Atlantic for a year, he was the one most susceptible to seasickness; at the ripe old age of 9, he is practically immune.

|

|

Markus Schweitzer lowers the flag as Namani departs Fiji. |

The culinary arts pretty much went by the wayside on those first days, and we vaguely remembered the good old days, when passagemaking meant a good book and the occasional batch of muffins. Now, we were in a constant game of Twister: right hand on the overhead rails, left hip bashing the corner of the chart table. Dodge flying cookie tin; spin again. A good thing to be said about short passages is that even when they get messy, the end is always in sight. Normally, we don’t start our countdown until the last miles of a passage, but in this case, it kicked in as early as mile 462 of 489!

Conditions gradually eased over day three for a smoother ride on day four. The swell had gone on to bully other sailors in another part of the ocean, leaving us with a gentle bounce — a warning that further mischief awaited, perhaps. We opted to keep the main reefed despite wind down to 15 knots, to slow down for a morning arrival. It was with a sigh of relief that we lined up the range markers and entered reef-protected Anelcauhat Bay on the south side of Anatom. Crews who arrived two days later made it under gentler conditions, but logged hours of engine time as the trade winds fell into a slumber. That’s yet another trade-off of cruising: comfort and speed versus budget. We’re not above kicking the engine on when we have no choice, but we generally try to spare diesel costs. In that sense, we certainly did pick a good weather window.

For the following month, we were enchanted by the people and landscape of Vanuatu, a magical place that earned top marks among so many Pacific highlights. We kept putting off our departure. One more island! Just one more! At the same time, we were digesting lessons learned. Continuing our intended course west to New Caledonia and Australia meant more south than west in our headings. The farther north we headed in Vanuatu, the less favorable the course to New Caledonia would be, given prevailing southeasterlies. For example, checking out of the islands at the capital of Port Vila would put Namani on a heading of 192°; going as far north as Luganville on the island of Espiritu Santo would make it 182°. So we swallowed the bitter pill of compromise and ended our Vanuatu adventures at the midway point of the island nation. The next passage to New Caledonia was only 330 miles — but by now, we knew enough not to expect either quick or easy.

|

|

Markus directs Nadine from the foredeck while anchoring in Vanuatu. |

Four’s company

It had been a long time since we had a friend aboard for an offshore passage, but we were happy to offer Danny, the twenty-something son of a fellow cruiser, a ride to New Caledonia. Namani now had a complement of four people. Hot-bunking and an extra plate to wash after mealtimes were more than worth the fine, fun company and an extra hand. With three adult crew, we now had the luxury of three hour watches and a full six hours off, rather than our usual four hours on, four hours off. The extra rest time was well appreciated because our familiar companion, the sloppy swell, seemed determined to give Namani a wild ride.

We knew the first 24 hours wouldn’t be pretty, but there aren’t many nice options for the trip from Port Vila to southern New Caledonia’s Havannah Pass. We decided to take the best from slim pickings and depart on an ESE wind forecast to go through the east and then to the north for a short time. The idea was to ride those winds for two days, then sit out a passing front and contrary winds with a pit stop in the Loyalty Islands. (Unfortunately, it is not possible to clear in to New Caledonia at the Loyalties, so most sailors bypass the islands or make brief, discrete stops.) Once the headwinds moved on, we hoped to catch southeast winds on the tail end of the frontal passage for the last 100 miles. Another great plan — on paper.

Of course, we’d learned to expect the unexpected, so the plan was more of a vague hope, anyway. And a good thing, too, because things didn’t develop quite according to the forecast. We did get 25-knot easterlies to blast us out of Vanuatu over the first 24 hours, along with the expected two-meter, short period swell from the beam. Namani banged along on a close reach and endured sneaky below-the-belt punches of the competing swell lines. Our generally miserable crew hung on to the hope of better things to come — and if not, well, 300 miles isn’t really all that far, not in the grand scheme of things.

Unfortunately, the frontal passage moved more slowly than anticipated, so that northerlies were still blowing when we hailed the island of Mare in the Loyalties. Without a good anchorage to shelter us from the north, we were forced to scrap our pit stop. The catch of a nice mahi-mahi did much to boost crew morale as we pushed straight on for New Caledonia — and straight into the frontal passage. Flaky winds and intense lightning storms marked the front, making for an electrifying night. Markus called it “intense periods of light punctuated by brief flashes of darkness.” Using the radar, we managed to sneak between the heaviest storm clusters and got through with nothing worse than jittery nerves.

|

|

Markus, Danny and Nicky admire a freshly landed mahi-mahi, the lone catch of the passage from Vanuatu to New Caledonia. |

Behind the front lay the southwest winds we had hoped to sit out in the Loyalties. Now tacking was on the menu as Namani inched toward a dawn arrival at Havannah Pass. The current there can reach four knots, so our timing was good for slack tide — with a little help from the iron genny. And once through — poof! — the slamming and grinding ceased; forward motion was no longer hard work but a pleasure. Having arrived on a Friday, we anchored in the quiet Prony Bay for a little R&R before continuing on to Noumea for a Monday clear-in.

Suddenly, we were in a completely different world. Having ducked under the curtain of clouds that cluster over Vanuatu, we emerged into a sunny new universe on the other side. Gone were the gray-blues of Vanuatu and the open ocean; this world was a startling aquarium of turquoise and pale blues. The lush, green heights of Vanuatu were replaced with the weeping red earth tones of New Caledonia. These testify to the island’s rich mineral deposits, as well as man’s greed in harvesting them. The tranquility and third-world charm of Vanuatu were behind us; we were back in France and a somewhat less endearing version of civilization. But New Caledonia’s lagoon was a thing of wonder, and we were thrilled to spend several happy weeks exploring its reefs and sandy cays.

|

|

Markus at the helm while coastal sailing in New Caledonia. |

Lessons learned

So what ever happened to short and easy? A lesson we had long since learned had been reinforced: it’s not distance but conditions that ultimately defines those terms. Our 3,000-mile passage between the Galápagos Islands and the Marquesas had been a dream of steady sailing in benign conditions, making those 28 days the “shortest” passage in our wake. In contrast, these three- and four-day hops seemed much longer. Part of the reason was our heading: southeast winds can seem a lot less friendly when the bow is pointing SSW instead of west. Beyond that, the southwest Pacific consistently served up a different kind of ride — almost like an ocean of its own, where the long, steady swell of the eastern Pacific was replaced by a confused slop.

What accounts for the swell? This stretch of ocean is several thousand miles west of the carefree playground we left behind somewhere in the vicinity of Bora Bora. It’s the home turf of the South Pacific convergence zone (SPCZ) and highly sensitive to the spillover of weather systems whisking by in the far south. The two can also gang up, for example, when frontal passages in the distant south connect with a branch of the SPCZ. Part of it may be a hemming-in effect: more islands, fewer swaths of open water to allow the swell to stretch out, plus an irregular underwater topography. No matter how much information we gathered on weather systems, convergence zones, wind and swell conditions, there was no predicting exactly how everything would align in terms of crew comfort. That’s the ocean for you. If we wanted predictable, we’d never have left home.

The lesson, I suppose, is not to underestimate the sea — any stretch of it, no matter how short. But the rewards remain the same: the pride of having covered yet another inch of the globe, and the unique landscapes — cultural and physical — at either end of the trip.

————–

Nadine Slavinski is the author of Lesson Plans Ahoy! Hands-on Learning for Sailing Children and Home Schooling Sailors (see www.nslavinski.com). Together with her husband and young son, she lives aboard her 1981 Dufour 35, Namani.