The return passage after the Newport Bermuda Race is often a pleasant cruise. It is usually well off the wind and without the constant pressure to make the last one-hundredth of a knot or change sails at the first (or last) possible moment. For me it’s a chance to catch up with old friends in the crew.

Rich du Moulin needed crew to bring his Express 37, Lora Ann, back to New York. I joined him along with two experienced sailing friends from my college years, Lee Reichart and Bill Rapf (all aged 65 to 67, but fit). This crew had more than 50 Bermuda races plus return passages. Rich is a prime mover in Safety at Sea training, so we knew that Lora Ann would be well found and well prepared for the passage. In the exhilarating reach that was the 2012 race, she finished third in her class to Carina, which won the St. David’s Lighthouse Trophy. Lora Ann has been on the podium for six straight Bermuda Races.

On Saturday, the day before our planned departure, the briefing room at the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club was packed for the presentation by the Bermuda Meteorological Service. The weather in Bermuda was benign, but the forecast showed two worrisome features. In the Gulf of Mexico, a developing low seemed destined to become a tropical storm, and perhaps a hurricane. A shower of computer projected tracks splayed out from its center. Most headed north to the Gulf Coast, but some crossed the Florida Peninsula and moved out into the Atlantic, crossing the homebound course late in the coming week. In fact, this low developed into tropical storm Debby and did follow the less probable track out into the Atlantic.

|

|

Ocean Navigator/Alfred Wood illustration |

|

While en route back to the U.S., a rig failure put the boat’s return to the mainland in doubt. An effective jury rig saved the mast, however, and allowed for a passage to New York Harbor. |

The other prominent feature was a strong cold front moving off the U.S. coast. As it closed in on Bermuda in the daily projections, it squeezed the isobars against the amoeba shaped western extremity of the Bermuda High. If we left on Sunday, southwest winds would increase to 25 to 35 knots on Monday night as we intersected the front — conditions Lora Ann had encountered many times. It would be a bit bumpy on Monday night perhaps, but preferable to a delayed departure that might encounter a developing hurricane later in the week. The skipper’s subsequent conversations with a private weather routing service confirmed the projections, and we left St. George late on Sunday afternoon.

Crew casualty

Two hundred miles out of Bermuda, as the wind was building, Lee, a veteran of 20 years racing on Lora Ann and many trans-Atlantic and Bermuda races, slipped and fell against the primary jib winch on the port side. As we reached farther away from Bermuda, Lee found it more and more difficult to move without severe pain, and by Tuesday as the seas built he was confined to his bunk, the pain buffered by Oxycodone and Valium. (Once home, X-rays confirmed a broken rib on his left side.) Rich had e-mailed his wife Ann, a registered nurse, who advised us on the drugs. She also gave us the symptoms for a punctured lung, which fortunately were not present.

As Lee’s condition worsened, so did the weather. Throughout Monday afternoon and evening, we shortened down from the No. 3 jib to the Solent to reefed Solent, and from full main to one and then two reefs. By dusk on Monday night, we were sailing with only the double reefed main.

|

|

Hans Johannsen/yacht Choucas |

|

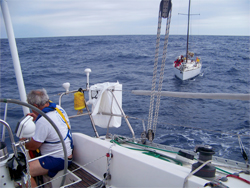

After a crewmember fell and broke a rib, Lora Ann suffered a shroud failure. Lora Ann’s crew rendezvoused with another yacht to take on extra fuel. |

A small boat that does a lot of around-the-buoy racing, Lora Ann has a mainsail fitted with a boltrope and slot — no slides. Her reefs are secured by shackling each reef tack to a strop near the gooseneck rather than hooks that tend to release the sail as it is doused. But above the second reef the luff can blow away as the sail drops out of the slot. With one man down, and one having to steer in the big seas (the autopilot was struggling at that point), two crew would be hard pressed to control the mainsail when doused, so we deferred putting up the trysail.

Lora Ann sails remarkably well, however, with a double-reefed main alone, and we had been through 50 knots with this rig on many occasions so we did not change to the trysail. Lora Ann powered on into the night on a close reach at full speed. As forecast, the winds built to more than 30 knots. The seas were clearly growing to impressive heights, and the self-steering gear could not cope, so we steered by hand. We were almost glad we could not see the full height of the waves. One boarding sea threw the helmsman across the cockpit, but the two men on deck were safely strapped in and Lora Ann held her course. Rich has a strict policy of all crew tethered from the time one begins to ascend the ladder to the cockpit until back down below standing on the cabin sole. There is a big padeye near the companionway for this purpose.

The damage

By dawn on Tuesday the seas appeared to be running 20 feet, with the wind holding the anemometer well up in the 30s. Bill and I were on watch. As the gray light grew, there was a sharp crack, like a rifle shot. I looked up from my cockpit reverie to see the lower windward shroud flapping free, and the unsupported mast violently flexing from port to starboard about two feet at the first spreader. The shroud had broken off near the deck. I yelled “tack” and Bill immediately put the tiller down. Lora Ann promptly tacked to starboard, putting the load on the new windward side, taking the pressure off the port shrouds.

|

|

Hans Johannsen/yacht Choucas |

|

Rich Feeley on the foredeck of Lora Ann with the boat hook attempting to pick up the messenger line from the sloop Choucas. |

This tack brought us into the heart of a passing squall, sending the wind speed well up into the 40s. For the moment, we were safe, but we were heading back for Bermuda. Could we keep the rig in the boat, repair it and return to our course for New York?

The port lower shroud turnbuckle threaded stud broke when the forged lower eye cracked. Fortunately the chainplate and barrel of the turnbuckle were undamaged. At the spreaders, the mast was bent 12 inches out of column but did not appear fractured or dimpled. Being so out of column, the compression of the rig and seas could bring the mast down at any moment. The mast would have broken quickly if we hadn’t tacked, but it was still in danger of collapsing.

The repair

The first task was to reconnect the remainder of the shroud to the chainplate. Rich leaped on deck, and using a short piece of green Spectra line saved for damage control, fished the chainplate and stropped the turnbuckle back together. In order to tension the shroud, he secured a second (red) line to the turnbuckle, led it down through the chainplate, through a large block (also kept for emergencies) back to the primary winch. With this winch, we were able to tension the shroud and take up slack in the strop. Lora Ann now had all of her rigging, but we were unsure how much load it could take.

With a temporary repair in place, we reported our predicament to other boats during our planned morning SSB radio contact. All offered help. After considering the option of returning to Bermuda, potentially encountering tropical storm Debby en route, Rich decided to carry on for New York. Lee concurred from his bunk.

We tacked back on to port, watching nervously as the load from the reefed mainsail came on to the repaired shroud. It held but we decided to motor until the seas subsided. With the mainsail down we were able to take a spinnaker halyard under the lower spreader and around the back of the mast to the port rail and winch it tight. The mast was now supported by the two lines to the turnbuckle and the halyard.

When the storm subsided the following morning, Bill, sporting a helmet and PFD as a flak jacket, was hoisted to the lower spreaders to inspect for cracks (none) and attach a strong Spectra line to the babystay toggle fitting which we also led to the rail and aft to another winch. The babystay was perfectly located to support the lower shroud and bring the mast back into column. We then unrigged the supporting halyard and hoisted the reefed main and Solent jib. Nervous but comfortable with our jury rig, we revised our plans to put as little pressure as possible on the mast. This meant carrying less sail area than optimal, and motorsailing when necessary. We carried extra jugs of fuel, but not enough to reach New York.

Two pit stops

Choucas, sailed by a double-handed crew that was friends with Rich, was the nearest boat on our radio net. They arranged to meet us and transfer 10 gallons of diesel on Tuesday evening. By the time we rendezvoused, a little before sunset, the wind was down but the seas still high. We motored cautiously under Choucas’ stern as they floated a line down to us. Once we snagged it, they released the other end attached to a five-gallon jerry jug of diesel, which floated easily. We pulled in the line and hoisted the jug aboard. We threw back the line and repeated the maneuver to obtain five gallons more. Choucas exhibited excellent seamanship and did not hesitate to come back to help us.

|

|

Hans Johannsen/yacht Choucas |

|

Lora Ann as seen from the deck of Choucas, following the transfer of diesel. |

It was clear that we could not maintain our original schedule of two-man watches. Lee was confined to his bunk, and the skipper was navigating, doing damage control and maintaining constant communications links. Fortunately, Lora Ann has excellent hydraulic self-steering gear that does as well as a skilled helmsman in all but the highest seas. Bill and I shifted to one-man watches, letting the autopilot steer. The man on deck maintained the look out and adjusted sails. As we gained more confidence in our jury rig, we added more sail, striving to maintain six knots plus with sail and power, but never pushing the boat to its normal performance. When we entered the Gulf Stream on Wednesday night, we shortened down to the storm jib in case we should encounter a squall.

By Thursday, we were through the stream and making nearly seven knots on a pleasant beam reach with just the Solent jib and double reefed main. Still, if the wind died, we would not have enough fuel to reach New York and get through the harbor. Just before dusk, friends on the Tartan 47 Glory overhauled us and transferred an additional 10 gallons of diesel fuel. In snagging the floating jerry jug, the telescoping aluminum boat hook parted but we were able to successfully complete the transfer.

Glory had Internet access and was able to track Lora Ann on Yellowbrick for the three days after the shroud incident. When we broke the shroud they were 80 miles astern. Our Bermuda Race navigator John Storck, Jr., in Huntington, N.Y., knew of our problem via e-mail from Lora Ann, and visiting the Yellowbrick site, identified Glory as the boat behind us on our track. He e-mailed both Lora Ann and Glory, putting us in e-mail and satphone touch with each other. Like many newer boats, Glory had no SSB. Thereafter they were kind enough to act as our “security blanket” and follow us until rendezvous three days later.

The reaching wind angle held through Thursday night, enabling us to maintain nearly seven knots with minimal pressure on the rig and no motoring. We raised the New York Harbor approach early on a steamy Friday afternoon, and were safely secured in New Rochelle before dinner, only a little more than five days out from Bermuda.

|

|

Hans Johannsen/yacht Choucas |

|

Bill Rapf pulls a jerry can of diesel on board Lora Ann. |

Other yachts

We later learned that Lora Ann was not the only yacht to suffer damage in that squally front. The C&C 41 Avenir lost her rudder at nearly the same time. Unable to steer or control the boat with a drogue or a spinnaker pole steering oar, the boat wallowed in the tumultuous seas. The crew eventually elected to abandon ship and was picked up by a passing cruise liner. Avenir was later recovered.

The well-sailed J-120 Mireille owned by Hewitt Gaynor is a regular competitor of Lora Ann in double-handed races. She was about 40 miles to the east during the storm, sailing under full mainsail (a much stiffer boat). In one squall she was knocked down beyond 90 degrees by a sea. Water from the boarding sea flooded out the navigation station. Mireille also hit a floating object and her sprit was shoved aft through a bulkhead. Fortunately no one was hurt and our Black Seal rum on board was unharmed.

There were also serious injuries to crewmembers on the return passage of three other Bermuda competitors. Convictus Maximus sent a crewman with a spinal cord injury back to Bermuda on a merchant ship, while the Coast Guard extracted injured crewmembers from Barleycorn and Conviction for medical treatment.

—————-

Frank “Rich” Feeley is an associate professor at Boston University and owns a 34-foot Jenneau sloop, Antigone.