By the morning of Saturday, Oct. 1, Dan Decker knew the long wait was over. For the past several days, he’d had his eyes glued to GRIB files and storm-track predictions, hoping that somehow Hurricane Matthew — which was rapidly developing into one of the most powerful storms ever recorded in the Caribbean — would nudge east or west far enough to clear him and S/V Uma, the Pearson 36 that he and his girlfriend, Kika Mebs, had purchased two years ago and sailed to Haiti from Florida a few months prior.

“We were on the Internet every day, checking, checking, checking,” he said. The forecast model was not budging from a predicted track that equated to a nearly direct hit from Matthew, possibly as a Category 5 storm topping the scales with winds of at least 137 knots.

Haiti might not seem like a very good choice to hunker down in for hurricane season. However, Decker, 28, a relatively new sailor on his first boat, had a strategic rationale for being there instead of Florida: He surmised that although hurricane-prone, Haiti, where Kika has family, possessed some of the best protected anchorages in the Caribbean and very few cruisers to compete for them. “So, I think you are actually much better off there,” he said. By contrast, in Florida, “if you are in a good anchorage, you are there with 200 other boats with questionable ground tackle and many of them unattended.”

Matthew was not going to settle for Haiti. It was destined to slash through the low-lying Bahamas on its way toward the U.S. East Coast. By the start of hurricane season in June, the annual cruisers’ migration to the crystal-clear water and white sand beaches of the Bahamas had long dissipated, with boats scampering back to U.S. and Canadian ports or continuing south through the eastern Caribbean. Nonetheless, Patrick Always, with his wife, Byn, and children Jaedin, 20, and Abyni, 15 — first-timers in the islands who arrived in January aboard their 1975 Norman Cross 46-foot trimaran, 11 Purple Monkeys — had decided to linger, staking out an anchorage in the cruisers’ mecca of Georgetown, Exumas.

“The Bahamas has a few good places for weathering a hurricane, and Georgetown is one of them,” Always said. “There are a series of hurricane holes at Stocking Island that provide nearly 360 degrees of shelter.”

Even so, while 11 Purple Monkeys did fine, nine other boats in those hurricane holes were damaged or destroyed, mainly due to mooring lines that chafed.

|

|

The barge and crane used to refloat La Luna. |

|

Barb Hart |

Other cruisers in the path of Matthew include Bruce and Rhonda Hoglund on the hard with their Lagoon 420 catamaran The Norm, in Palm Beach, Fla.; Barbara Hart and husband, Stew, 250 miles north of the Hoglunds in St. Augustine aboard their 1985 Cheoy Lee Pedrick 47, La Luna; and Skip Gundlach and wife Lydia on Flying Pig, a Morgan 461, in Beaufort, S.C.

All these sailors faced, to some degree, a serious threat to their vessels and possibly their lives as it became clear that Matthew was bearing down on them. However, with good preparation and a bit of luck, they all managed to weather the hurricane with no loss of life and no major damage to their boats.

Modern weather forecasting gave each of them about a week of warning, though Matthew proved difficult to predict both in regard to where it was headed and how strong it would be when it got there. Partly for this reason, everyone interviewed for this story decided to stay put rather than attempt to outrun or outmaneuver the massive storm at sea.

In Haiti, Decker said he felt secure where he was in Petit-Goave, about 35 miles west of the Haitian capital, Port-au-Prince. But there were other considerations to take into account. About a week before Matthew hit, Kika had to fly to New York to tend to her mother, who was sick in the hospital. Making matters worse, the autopilot on Uma was broken. “So trying to single-hand away from a hurricane really didn’t seem like a good idea,” he said.

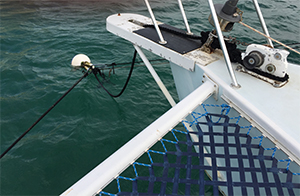

Instead, he stripped everything he could off the boat to reduce windage, including canvas, sails and solar panels. He also dropped Uma’s massive 105-pound Mantus anchor. Concerned about chafe, Decker attached not one but two rodes, each about 40 feet of 3/8-inch chain attached to 150 feet of 3/4-inch nylon line.

As the eye of then-Category 4 Matthew passed about 60 miles west of him with winds of more than 113 knots on Tuesday, Oct. 4, Decker, who remained aboard, experienced 80-knot gusts, but the sustained winds were in the more manageable range of 40 to 60 knots. He attributed it to the protection afforded by the mountains to the south of him.

|

|

Patrick and Byn Always’ multihull 11 Purple Monkeys rode out Matthew in an anchorage in the Bahamas. |

|

Patrick Always |

His most vivid memory of the experience came after the storm passed. “Everything smells like dirt or mud,” he said. “And then there’s the occasional dead animal floating by in the water.”

Bruce and Rhonda Hoglund on The Norm near Palm Beach were on the hard at Cracker Boy Boat Works getting major work done when the storm approached.

“We had already had our mast removed to replace the standing rigging,” Bruce explained. “We removed the dodger and tied down our large solar panel davit with ropes and a heavy-duty tow strap.”

His biggest concern? Storm surge. “If the 10- to 12-foot predicted surge materialized, [the hardstand] would turn into a shallow boat bumper-car lot, where the 170-foot megayacht seaward to us would shepherd smaller boats like us into the inland residential area, and likely provide stunning TV disaster footage showing our resting place in someone’s living room.”

As luck would have it, Matthew “wobbled” and edged east. Palm Beach got no more than a sustained 45 knots with gusts of up to 65 knots.

Skip Gundlach on Flying Pig in Beaufort, S.C., chose to ride out Matthew on a mooring that held steady despite the 90-knot winds recorded there.

“With the new and very stout moorings here, we moved to one and attached four very sufficient lines,” Gundlach explained — two 1-inch braided lines and another 3/4-inch in diameter. A fourth line was 1-inch three-strand, and all were protected with fire hose as chafing gear, Skip described. “Our boat has four cleats forward, so we attached one line to each.”

They lengthened the lines until “they could not slip under the keel … but would be long enough to handle the anticipated storm surge.”

|

|

The mainsail lashed in anticipation of the storm. |

|

Patrick Always |

The Harts’ La Luna also weathered Matthew in the mooring field at St. Augustine, but they were not as lucky as Gundlach.

The couple had considered acting on a recommendation to move up the San Sebastian River, but their options narrowed considerably when a test of the engine resulted in a blown muffler housing. “We would have had to call for a tow to move into the river and arrange to get on a dock. All of this was late in the process and we weren’t sure there would be a space for us on Wednesday. We had to make a decision quickly,” Barbara Hart said.

By then, they’d already removed everything from the deck, secured the wind generator, removed the bimini and dodger, and added chafe gear to the mooring lines. Goodbyes were said to La Luna and the couple headed inshore to a safer location.

It wasn’t enough. The 60- to 80-knot winds that hit St. Augustine generated steep chop and storm surge. Many of the moorings were simply not up to the task. The Harts’ boat was one of some 30 that broke free from moorings at St. Augustine and washed ashore. Theirs and two other nearby boats were pushed up on land with mooring balls still attached. “Ours is one of the least damaged. She did not hit and was not hit by another boat,” Barbara said. “La Luna floated on surge tide into shore and appears to have settled slowly onto her port side as the tide receded. One stanchion pulled out as it fought with a tree branch. That is the only damage.”

Hart’s advice to anyone finding themselves in a similar situation? “If you can’t add an anchor, or it’s not possible to add scope to the mooring, then don’t stay on a mooring.” What happened to La Luna, she said, “is a direct result of storm surge and waves.”